Episode 3: Illuminating the Dark Ages

In the previous episode we looked at the impact of Roman expansion on ancient people living in the lowlands and around the river Rhine. Roman influence began to wane already in the first century CE. In the 2nd, 3rd and 4th centuries varying regional powers rose and fell, operating with relative autonomy from whatever power Rome was able to wield at whatever time.

The continual movement of people from even further beyond the reaches of Rome to within its established and imagined borders, brought ethnographic change. Germanic, Gallic and Celtic peoples south of and immediately in the vicinity of the Rhine, who had survived the social and economic onslaught of Rome over the preceding few centuries would by 400s have developed cultural and social traits derived from that influence. But the Germanic groups moving across the Rhine and through Gaul from the hinterlands would have also mixed with those already there, and this miscegenation would have also had a major impact on the development of cultures around the Rhine delta during the twilight centuries of the Western Roman Empire.

Things were getting dark, as the so called dark ages had arrived. However, contrary to popular imagination, very many important and enlightening things were happening in the lowlands, which would affect the rest of Western Europe.

Episode artwork by Steven Straatemans

Already by the 3rd century Rome faced so many problems. The logistics of administration and controlling such a large empire was nigh on impossible. Furthermore, trying to engender a sense of Roman identity within such a multi-cultural and vast territory was a problem. We would get into the details of the collapse of Rome, but nobody could ever build a podcasting career out of that topic. So let’s just say that it happened, and it changed everything in the area we care about, the low countries. Woo!

From the 3rd to the end of the 5th century Roman control fluctuated before it eventually disappeared from the lowlands. Although the taxes levied by Rome disappeared, so too did its benefits. Infrastructure that they had built fell apart and disappeared, as did Roman administrative structures, now defunct. The power vacuum the Romans left behind created opportunities for new groups and individuals to step up and fill it. Struggles for domination between these groups would have been near constant, except for the periods when one gained a degree of regional hegemony.

One of the many groups inhabiting the northern lowlands were the ancient Frisii, however they too would disappear. It isn’t exactly certain what happened to them. The historical record of that exact tribe stops with something called the Twelve Latin Panegyrics - a panegyric being an official, public speech. These are thought to have mostly originated out of Gaul somewhere around the end of the 3rd century, and one says that the Frisians were forced to resettle inside Roman territory as laeti, which are kind of barbarians-made-serfs.

Another theory is that from the mid 200s, tectonic plate activity, storm surges, rising sea levels and subsequent recession of landmass caused huge floods of the area inhabited by the Frisii. Perhaps the mass inundations to which they were exposed forced a Frisian exodus into the southern lowlands.

Confusingly, the name Frisian will continue, but we will get to that.

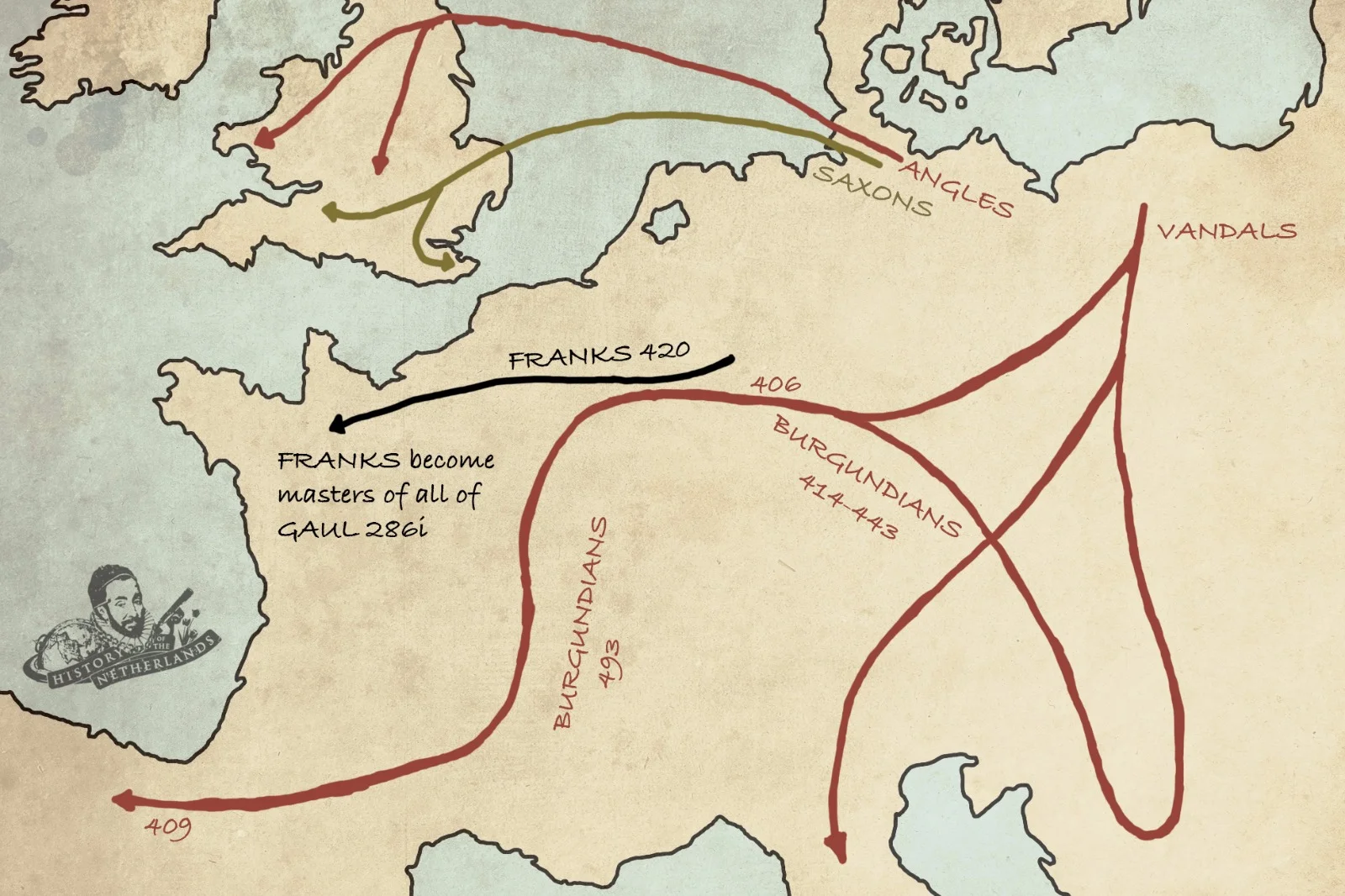

With the collapse of Rome something called the Great Migration occurred across Europe, whereby many different Germanic and Hunnic people began to move into the former Roman fringe territories, from all directions. Around the 4th and 5th centuries groups of other Germanic peoples began to move into the Rhineland. In 407 CE Roman troops left Britain, and so Germanic peoples set out to these now abandoned pastures. The main groups of these were the Saxons and the Angles, which we can refer to together, if you like, as the Saxo-Angles. Or the Anglo-Saxons, whatever. Also, the ever roaming and threatening Visigoths were encroaching upon the Rhineland and river delta region as well. It’s probably modern sensibilities, but a bad case of Visigoths just sounds bloody terrible.

It has been a long-debated issue as to how much Anglo-Saxon influence was brought to bear on the lowlands and, in particular, Friesland. Perhaps people living in Friesland since the 3rd century have actually just also been Anglo-Saxon. If the original Frisians had really been removed as serfs, just as the 3rd century Panegyrics had said, then perhaps their abandoned, flood prone lands were taken over by these migrants from the east. Archeological evidence and a change in Frisian architecture suggests a very strong Anglo-Saxon presence in Friesland from this time, so maybe the Fries had really disappeared. Any Frisian listening to this right now would definitely be thinking of throwing their cow at me, which I could understand. But don’t.

The Frisian name and sense of identity, however, sustained itself during a time when so, so many names and people did not, suggests that the original Frisians were not simply supplanted by pesky Saxo-Angles. That the Frisian name continues to this day suggests that, rather than a take-over, there was an integration of Angles and Saxons, and likely a myriad other Germanic and Celtic peoples, along with their own cultural quirks that over centuries became absorbed within wider Frisian culture. After all, the Anglo-Saxon culture of Britain that would emerge from this time also incorporated the culture of the indigenous British peoples who were there before them. And to my shame I don’t know a single one of their tribes’ names off the top of my head. Actually there were the Picts.

Anyways, in the latter half of the 4th century CE, Roman historian Eutropius, wrote of a people called the Franks. He tells us about how Constantine I, eventual father of the eventual Roman Emperor Constantine the Great, achieved great military success against the Franks along the Rhine river in the 290s and early 300s, and also of “Frankish pirates”, raiding off the North Sea Coast.

In the struggle for regional dominance that would be a constant in the lowlands during and immediately after Rome’s collapse, the Franks, alongside the Frisians, would be swinging the biggest and longest lasting punches.

The Franks are generally thought to have originated out of various groupings of Germanic people living in the lower and middle Rhine regions who confederated sometime in the early 200s. One candidate is that they came from the ancient Frisii fleeing from floods. From today’s Bonn in Germany, down the Rhine valley region and into the Netherlands towards the mouth of the great river. Like with most labels applied through history, the Franks were not a single, culturally or linguistically unified people, but the label is more of a way for us to identify groups of people whose details are mainly lost to us. There were many kinds of Franks, to be perfectly frank.

At around the same time Eutropius was writing - the late 300s CE -, another Roman man, a soldier-cum-historian called Ammianus Marcellinus, was compiling a comprehensive History of Rome that he would call Res Gestae. He also wrote about the Franks, but was the first to mention a distinction amongst them as a cultural group. Specifically, he identified the Salian Franks, a dominant lowlander group who would leave a very, very large imprint on this brave new world sans Rome. Because the Salian Franks, it is generally agreed, would go from being footnotes in the history of Rome, to founders of the Merovingian Era in Western Europe, taking guardianship of the transition from the classical age towards the medieval.

Germanic tribes spreading across Europe after Rome’s collapse. Map by David Cenzer

It’s early in the episode to do this, but hey, may as well get it out of the way. Much of modern, western Europe would be defined by what these lowlanders did. Even the modern country of France carries its name because of the rise of these Franks from our beloved swamp. So there you go. France, bet you didn’t know that was Dutch!

The Salians began to rise to prominence in the 4th Century CE. We know, according to Ammianus, that they had established themselves in Roman territory in the 1st century BCE, in an area called Toxiandria, today around where the Dutch province of Zeeland and the northern Belgian region of Flanders meet.

Their social system was one of extended familial tribes who formed a loose confederacy with other lowlander tribes, of people who would only unite occasionally, as the situation and their own particular agendas warranted it. The tribes centred on certain noble families, who were noble because they claimed they were descendents of Wodan, a badarse Norse God who was always accompanied by two ravens and after whom the day Wednesday is named. Wodan’s day. By the way, I too am a descendent of Wodan.

As they expanded their power base, and conglomerated with other groups, they absorbed the peoples around them, such as the Batavians, about whom we spoke in the previous episode. One can assume that, given the Salian Franks’ proximity to the sea, their culture, traditions and methods would have been similar to those who preceded them, living in an area where the land, ultimately, will always be threatened by the sea. Building primitive dikes, canals and dams would have been as much their lot as that of every other person inhabiting the lowlands over time.

So, not exclusively by any means, but by the 5th century there were the Salian Franks in the lowland Rhine delta, and the Ripuarian Franks, further up the Rhineland, around modern day Cologne. It is unknown how the two groupings related to each other. Despite the decline in international commerce that was also a consequence of Rome’s collapse, one can suppose that regional trade was sustained and that the lowlander Salian Franks and less-lowlander Ripuarian Franks exchanged materials with each other, as well as with the other groupings of people in their trade accessible proximity. Inter-marriage and alliance systems also more likely than not occurred from time to time.

As we said, the Franks themselves were a collections of peoples, They would have identified as and called each other by many different names, most of which we will never, ever know. They also would have had a wide and diverse variety of ideas and beliefs, bearing various degrees of Germanic heritage and Roman influence. However, a new force was about to enter into the social fabric. It would be bigger than Rome, last longer, and go further. It would come to dominate every single one of these groups, and lay particularly fundamental paving stones in the road towards the middle-ages. We’re speaking about, of course, the Jedi. Actually it was just monks. Christian monks. They do wear similar robes though.

Religion and spiritualism amongst the varying Germanic, Gallic and Celtic peoples of Rome’s hinterlands originated in far ancient Indo-European polytheistic paganism with peculiar and particular influences. These would have been picked up and carried around the continent over thousands of years of migration and miscegenation. Some had religious orders, such as druids, some did not.

The Roman influence on the outskirts of its empire also included the realm of religion. The Graeco-Roman pantheon was, to different, varying degrees incorporated over time into the different and mixed Germanic, Celtic and Gallic groups. With those came echoes of the Hellenism that already a thousand years before had collided the Greek world with that of Egypt and Persia, which had had its own impacts on Rome. Like a big spiritual buffet where you can pick and choose gods, like Wodan, who we mentioned, or Donar, also known as Thor, who was another badass Norse God who was apparently raised by two lightning spirits. He got the day Thursday named after him. By the way, I am also a descendent of Donar. Bow to me. Mythological figures were specific to certain clans, areas, and purposes. In Zeeland, for instance, Nehalennia, the goddess of travellers, was widely worshipped, also in regard to her influence over shipping, trading and other things of a maritime nature.

The Christian Gospel first appeared in the lowlands some time in the 4th century. Christianity had already undergone centuries of various degrees of oppression and acceptance in the central regions of the Roman empire which, although beginning its western decline, still, by far, swung the most weight around the continent. In 313, under the supervision of Emperor Constantine, the Edict of Milan decreed that Christianity would thereafter be tolerated, and a process began to try to deal with schisms within the religion. In 325 official dogma was declared in the first Nicean creed. Constantine also famously became known as the first Roman Emperor to convert to Christianity, even though this is matter of debate.

The point here, for us looking at the various Germanic, Celtic and Gallic peoples in the lowlands, who were converging into an identifiable identity as predominantly Franks, is that Christianity had moved from being an illegal, underground movement, to having the sanctuary of the state, and so protection to grow and spread. From this point for the next 1500 years, the welding of Christianity to the mindset of every human in Europe would be the mission and accomplishment of countless monks, missionaries, nuns, and other members of an ever-more established clerical structure set for domination of the spiritual realm. Even out on the fringes of this new world, the lowlanders would be no exception to exposure.

Servatius of Tongeren was an Arminian diplomat who, in his work for the emperor, would travel widely and eventually settle in and around Maastricht, in Limburg, where he died around 384 CE. He became the Bishop of a very early Christian diocese of Tongeren, and is believed to have built at least two early churches, in Tongeren and Maastricht. Excavations in Tongeren have found the remains of a 4th century church, supporting this claim, so certainly by this time there was at least a tenuous foothold in the lowlands for the religion that would eventually surpass all others.

In the 5th century Germanic tribes like the Saxons and the Angles, as well as Visigoths and Alemanni, were making continual incursions as well as organised invasions of Friesland, Brabant and Flanders. In around 450 CE, Childeric, the son of Merovech, defeated various of these tribes and established a dynasty that would bear the name of his father, the Merovingian dynasty. His son, Clovis, would go on to unite all of Gaul. He became the leader of his tribe at 15 and, considering that he and all his family members could claim descent from Wodan, he went about killing them all. In 5 years he had united all Frankish peoples, and all of western Europe except for Burgundy in the south-east of today’s France, the Frisians in the north and the Saxons in the North-East. He also created Salic Law, a codification of civil law that would form the basis of Western European law significantly in the middle ages and still somewhat today. Manuscripts relevant to Salic law that survive, dating as far back as the 6th Century, include possibly the oldest written examples of Old Lower Franconian, or Old Dutch.

The Merovingians, in their push south, moved their centre of power over the next 300 years away from the lowlands, their flood-prone swamp of origin. In around 496 CE Clovis converted to Christianity, following the lead of his wife. Christianity was now the official establishment religion, the choice of kings, and this raise in the church’s stock would not be avoided by the lowlanders over the next centuries. The centuries after would see the expansion and creation of different dioceses, and increased power being put in the hands of bishops. Furthermore, Merovingian kings distributed their inheritance amongst their sons, by custom. The dilution of power, coupled with the establishment of lords and committees over time, meant that real control was appropriated by dukes and counts - members of the king’s court, with fancy titles such as majordomo, Mayor of the Palace - After three centuries the Merovingian kings had become mere ceremonial figureheads.

We often look at this bit of history as the story of these Frankish kings, and so concentrate a lot on things like how they began a culture of dividing inheritance. This meant that after a king’s death, the kingdom would be split between sons, rather than just inherited by the eldest,This was a terrible idea and would lead to a whole lot of problems, which the next episode will go into in great detail.

But for now, in this episode, we care about the people who remained in the swamp; the lowlanders, who were looking after their cows, making cheese, thinking big thoughts like whether in the future shoes might be made of harder materials, fishing and, crucially, beginning to engage in trade networks that were ever widening across Europe.

Dorestad was a trade emporium set up somewhere in the 7th century, not far from Utrecht. About 3km2, fairly large for a settlement of the period, it represented the mercantile viability of the lowlands as much as any of the major towns that would follow. Dorestad sat at a river junction in the Rhine, and from there markets in France, Germany, Britain and Scandinavia could be accessed. You can imagine it as a bustling town where loads of both luxury and staple goods would be coming on and off boats in the river, haggled over, and carted off somewhere else on a constant basis. People, animals and all the goods between them, living on the banks of a flood-prone river, dependent on the canal and dike systems that they and others had built.

So coming into the 7th century, the region was dominated by the Salian-Frankish and Christian Merovingians in the South, themselves becoming ever more fractured, but still in an expansive mode, and the still-Pagan Frisians in the North, who may or may not have actually been some degree of Anglo-Saxon.

Control over Dorestad and other settlements on the Rhine, like Utrecht, exchanged hands between groups of Franks and groups of Frisians many times over the 7th and 8th centuries. In fact, during periods when they ruled it, Dorestad allowed Frisian merchants to expand their influence so greatly that in much of northern Europe the North Sea became known as the Frisian Sea. They built trade colonies in Mainz, York and London, using the rivers and the sea to their utmost advantage. And they did all this while, in the flood areas of Friesland proper in the north, there was basically no trade at all. Just cows

Despite this mercantile strength, however, the Frisians could not stop the Merovingian Franks, who had come out of the lowlander Salian Franks anyway, from pushing once more into the delta, north of the Rhine, and into the Frisian lands.

The last Merovingian king to wield any actual power, and not just be a ceremonial figurehead, was Dagobert I. At some time during his rule, from 629-639, the fortress of Utrecht was captured by Frankish forces. Dagobert built a church there, intending to begin the process of Christianising the Frisians. He entrusted this church, and so the surrounding region, to the care of the Bishop of Cologne, with the proviso that he undertake the conversion of Friesland.

This clearly did not occur. The Frisians would become known as the last peoples in Northern Europe to cast off their pagan deities. An English Benedictine monk, Bede, writing around the turn of the 7th into the 8th centuries, tells us that in 678 CE, some forty years after the initial attempt by the Franks to Christianise the Frisians, they were visited by Wilfried, the bishop of York, who had been travelling from England to Rome but whose ship had been swept by wind into the pagan lands of the Fries. He was met by a Frisian king, the first mention of any such person or position, and apparently stayed there to convert as many as possible.

This saw little success. So, ten years later, more missionaries were sent into Friesland, which was now under the rule of a guy called Radbod. Not to be confused with Dad-bod. He went about taking Utrecht and Dorestad back from the Franks and in the process, destroyed the church in Utrecht, vehemently asserting their right to remain pagan. The Frisians were proving more than a little difficult when it came to converting to Christianity.

In 690 a twelve-man-strong jesus-strike-force landed in Friesland headed by the Anglo-Saxon missionary Willibrord. Once again their mission was to convert the barbarous Frisians, but now they turned south to the Franks to look for support, which they received from the now Frankish king, Pepin the Younger.

In the 690s, Pepin’s Frankish forces drove Radbod and the Frisians out of Utrecht. After a trip to Rome, Willibrord was appointed as the first Bishop of the Frisians, and on his return to Utrecht he began building a cathedral there. It seemed as though the conversion of the Frisians would be a certainty.

However, Willibrod never had much luck, even in his territories south of Utrecht, and would, after ten years, relocate to Denmark. Radbod remained a dominant ruler of Friesland, and stubbornly stuck with the old gods. One story relates how he was almost converted to Christianity, but at the last moment changed his mind, declaring that he would rather spend eternity in hell with his fallen countrymen than be in paradise with the Christian foreigners. Pepin the Younger, meanwhile, died in 714, throwing the Frankish kingdom into the usual turmoil when his inheritance was divided between his sons.

The insatiable Radbod took the opportunity to retake his lost possessions of Utrecht and other settlements along the Rhine. Some monastic annals tell of him having sent a force as far up the Rhine as Cologne, and defeating the famous Frankish warlord Charles Martel. Churches across the lowlands were destroyed, and the Frisians were in control.

But Charles Martel did not become famous because he was an easily defeated foe. The Frankish leader was very good at coordinating his regime with the church. In 719 CE, Radbod died, and so the church’s biggest opponent in the lowlands was no longer an obstacle to its expansion. Willibrod returned thereafter, with his assistant, a little known would-be-saint called Boniface. Together they went with zeal and good faith once more to Utrecht, and into Friesland. They themselves now stamped out pagan sites, and set about spreading the word.

Charles Martel took the opportunity to go on an offensive against the Frisians, pushing up to the Rhine and putting the reclaimed diocese of Utrecht under Christian Frankish control. He took care to protect Christians, and endowed Willibrod and Boniface with a lot of perks and gifts to their church in Utrecht. In 734 CE, he then took a naval force into Friesland and defeated their new leader, Bubo.

In 739 CE Willibrod died, leaving Boniface to create the religious, rather than aquatic, Frisian see out of the scramble for power that would ensue. Over nearly 20 years he and Willibrod had set about achieving something that the Frisians had avoided for so long, conversion. But now, the Bishop of Cologne fetched his records from the previous century and all of a sudden claimed that the Christianisation of the Frisians meant that they would come into his diocese. Boniface quite rightly stood up and told him where to go, in the most saintly terms, of course. He argued that none of Cologne’s bishops had been responsible or active in the conversions, and that this was the original stipulation on any right they had to the see.

The tumult around this issue continued for the next 15 years. In 754 CE, at over eighty years of age, Boniface was still active in his mission, smashing pagan sites, building churches, and preaching. When he and a party of over 50 others were surrounded by bandits whilst travelling one day, he ordered his party not to resist, and 53 of them were killed. Maybe that wasn’t the best decision he ever made.

When the Franks in the south heard of this, they took to blaming the Frisians, and being generally very angry. Expeditions into the territory from which the bandits had come saw countless people who had had nothing to do with Boniface’s death face punishment for it.

In terms of the centuries long tussle between the Franks and the Frisians over control of the lowlands, this was now a turning point. Enough of the Fries had been brought into the realm of the church for Frisian independence to survive the amalgamation of social and spiritual hierarchy. In Dokkum, right in the north of Friesland, there is an ancient church that memorialises the last of the Frisians conversions taking place there in 772.

The people of the lowlands, particularly the Frisians, being in the corner of Europe, had managed to avoid the spread of Christianity for longer than nearly every other northern European peoples. But finally they had come into line with the a religio-social order that would reign for the next thousand years. Since the fall of Rome countless efforts had been made to fill the vacuum, with no one group achieving it completely. But now, one of the people most influential in the course of European history, was now centre-stage, and setting himself up right around our little swamp, filling that vacuum.

Charlemagne will become known as the father of Europe, and will lay the foundations of medieval feudalism. But we’ll hear all about that in the next episode.