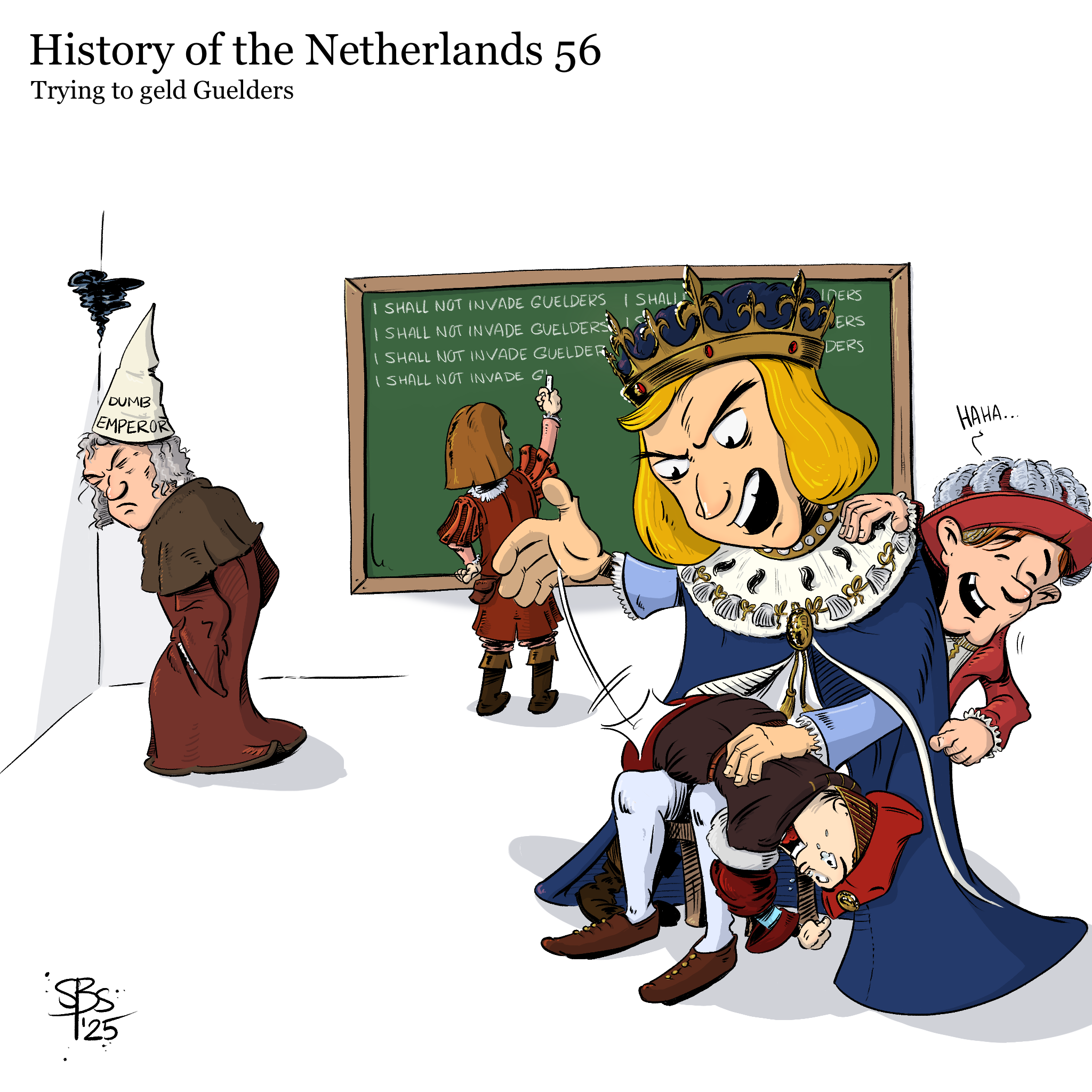

Episode 56: Trying to Geld Guelders

Many thanks to friesekerken.nl for supporting this episode. Check out the website and sign up to become a donor to their foundation which helps preserve monumental churches in Friesland.

Around the same time that Friesland succumbed to the rule of a foreign prince in 1498, the Duchy of Guelders was also engulfed by a struggle against Habsburg domination. Charles of Egmont and Emperor Maximilian both continued to lay claim to the title of Duke of Guelders and over the next half a century, the conflicts in both Friesland and Guelders would become inextricably linked in a series of on-again, off-again wars. To begin this episode, we will take an unexpected but delightful detour to a part of Europe that doesn’t naturally come to mind when you think of Guelders… Italy! There we will see Maximilian fail to impose his authority on a conflict between Pisa and Florence. Bentornati al podcast sulla storia dei Paesi Bassi. After that we will see Maximilian enlist the help of two German princes, the Dukes of Julich and Cleves, to try and bring Guelder to heel and carve it up between them. In this, Maximilian will also fail to impose his will, this time facing resistance not only from Charles of Egmont, but also his own son, Philip the Handsome. Finally, we will see how Charles of Egmont benefited from a bit of French mediation in the war between Guelders, Julich and Cleves, before he almost met an untimely end at the siege of Huissen in 1502. There’s a lot to get through! So let’s get cracking.

“Trying to Geld Guelders” episode artwork by Steven Straatemans

To begin, let’s recap where we got to when we last focused on Guelders. In Episode 47, we saw how Maximilian and Charles of Egmont had traded blows throughout the early 1490s as they both ran around, each proclaiming to be the sovereign ruler of Guelders. Maximilian had attempted to use the influence he wielded as Emperor to resolve the issue at the Diet of Worms and later in the Reichskammergericht, the Imperial Court in Frankfurt, but Charles of Egmont simply refused to travel there when summoned in 1496. Fair enough too, since Maximilian essentially presided as judge of the court. It was around this time that Maximilian’s eyes turned to matters elsewhere - namely in Italy. His son Philip, who ruled the Low Countries as the Duke of Burgundy, was often more influenced by his advisors than by his father - as one appellation given to him, Philip croit-conseil (and the name we gave to episode 47), implies. When it came to Charles of Egmont and Guelders, he took a more conciliatory approach. That’s where we left the situation in Guelders in that episode, in a stalemate, where it looked as though the only way that the big question of sovereignty over the territory would be solved was with a lot of pointy swords.

Maximilian gets distracted by Italy

After a period of diplomatic wrangling had failed, you might assume that Maximilian would head into Guelders all guns blazing to rid himself of Charles of Egmont for good. By now though, Maximilian was effectively the Emperor, meaning that he had a whole bunch of other things on his mind. Furthermore, if we have learned anything about Maximilian, it’s that he definitely had grand designs on himself and his position in European affairs. So it was that, rather than bringing the Guelderian matter to the fore, he found himself embroiled once again in the affairs of Italy, this time in the matter of a war between Pisa and Florence.

We last found ourselves in Italy during Episode 48, when we spoke about the French King Charles VIII’s campaign through it in his attempt to take over the Kingdom of Naples. On his way to Naples, Charles VIII and his army had traipsed their way overland across Tuscany, plundering the countryside, destroying castles and occupying various cities and strongholds. Charles VIII had entered the town of Pisa in early November, 1494, being met by an enthusiastic populace. Pisa had lost its own independence to Florence in 1406. So when Charles VIII was in Pisa, the people of the town begged him for liberty from Florence, to which he apparently agreed. In their book The Italian War 1494-1559, Christine Shaw and Michael Mallett write that “he may well not have understood the full implications of what he agreed to; perhaps confusing the ‘liberty’ for which the Pisans pleaded with the ‘liberties’, the privileges, enjoyed by the civic authorities of towns in France.” Imagine that; having a linguistic misunderstanding with a Frenchman. When Charles departed Pisa the citizens exercised their fresh, new notions of liberty and immediately chucked out the Florentine officials, reasserting their independence.

When Charles VIII rocked up in Florence a few days later, that city had just had their own revolt in which they had deposed their Lord, Piero D’Medici, also known as Piero the Unfortunate. The Florentines had risen up in anger because Piero had agreed to surrender various fortresses to Charles VIII’s army, including Pisa and also Livorno. Charles made an agreement with the miffed off people of Florence that in exchange for a bunch of cash, he would give them those fortresses back as soon as he had captured Naples. But instead, when the French king left Italy in October 1495, the lieutenants he had left in charge decided to engage in a bit of old fashioned corruption and turned their attention to extracting as much profit out of the region as they could. Only the fortress of Livorno, which sits on the coast close to Pisa, was returned to the Florentines. In January, 1496, the French commander in Pisa, Robert de Balzac, decided that he would rather sell the fortress to the Pisans for 20000 ducats, and a few others to Genoa and Lucca, than give them back to Florence. You might say that he acted like a real ball sack. Pisa had been given the money to do this from Venice and Milan, who were both happy to hamper Florence, unhappy as they were that Florence had given Charles VIII support in his Naples expedition. As a result, Pisa was loaded up with troops from Venice to defend it against sporadic attacks coming from the Florentines.

A contemporary account from the time titled A Florentine Diary from 1450 to 1516 by Luca Landucci is filled with tidbits regarding the divisions inside Florence at the time, and illustrates how unhappy they were about not getting their fortresses, particularly Pisa, back. In the power vacuum that followed Piero the Unfortunate being booted, Florence had come under the sway of a radical Dominican friar called Girolamo Savanarola, who is seen by some historians as a proto-Protestant. Savanarola declared that Florence would be a New Jerusalem. Some inside Florence blamed him for their misfortune, marching around the city at night chanting “this wretched pig of a monk, we will burn the house over his head”. Over the next few months, pressure ramped up inside Florence over its own internal struggles, the war with Pisa and about whether or not they should join the Holy League that Maximilian and the monarchs of Spain had formed against Charles VIII.

Around this time there were also rising tensions over the title of Duke of Milan. The man who actually ruled in Milan, Ludovico Sforza, had usurped the title after the death of his nephew through marriage, Gian Galleazo Sforza, for whom he had been ruling as regent. Charles VIII’s cousin Louis de Orleans (who was soon to become King of France himself), had a strong claim to the title through descent, being a grandson of Valentina Visconti, whose family had ruled Milan for two centuries. Ludovico had originally supported the French in their invasion of Italy but after the death of his nephew he had switched sides and joined the Holy League. In May, 1495, Ludovico was officially invested with the imperial title of Duke of Milan by Maximilian. In July 1946, as he was fretting about a potential French invasion of Milan, Ludovico decided to ask Emperor Maximilian for help and invited him to Italy. They met in the mountainous area of Tyrol where, according to historian Cecilia Ady in her History of Milan under the Sforza, “Maximilian did his best to treat the whole affair as a pleasant hunting party rather than as a diplomatic negotiation.” Ludovico still succeeded, however, in getting Maximilian’s agreement to once again go to Italy to fight the French, though Maximilian succeeded in charging Ludovico 40000 ducats every three months for the pleasure.

Maximilian goes on a Tuscan adventure

To initiate his now forthcoming Italian campaign, Maximilian went to Germany to try to drum up support from across the empire for the scheme. This was unsuccessful, since the princes of the empire were largely not on board with the idea. Maximilian’s son, Philip the Handsome, travelled from the Low Countries to meet Maximilian in Augsburg. Much like his father, Philip also enjoyed the finer aspects of life. In History of the Latin and Teutonic Nations, Leopold von Ranke writes: “At Augsburg, where they made a pile of maypoles and garlands forty-five feet high for the St. John’s Day bonfire, the finest damsel with a wax taper in her hand kindled it with him in the dance, whilst the trumpets, cornets, and kettledrums all brayed to the fire and the dance.” Bloke’s just gotten married and here he is skipping around a fire, kindling some hot maiden’s taper. After these jollies, Maximilian then informed Philip of his plan, which was to attack the French by disrupting their support from Florence. Von Ranke continues: “He hoped to keep the French back from Italy and Livorno; Florence would then league itself with him; nay more, aid him to cross over… from Tuscany to Provence. This done, Philip should invade France from the Netherlands and Ferdinand (of Aragon) from Roussillon. At Lyons, they might all three meet, and then Burgundy would be won”. This was, of course, a strategy that worked best in Maximilian’s wildest late night fantasies. In reality, the expedition would only involve an attack on France’s allies in Italy, Florence, at their stronghold of Livorno.

In August 1496, Maximilian entered Italy with a very small army, with one source saying around 200 horses and about 1000 men, expecting to be mostly supplied with troops from Venice and Milan. It turns out, however, that those two cities were also pretty big rivals with each other, and were wary of giving too much help to Maximilian lest it should inadvertently aid the other. Early twentieth century historian Cecilia Ady wrote “It has been well said that, of all Maximilian’s schemes, “none were more fantastic and fruitless than the enterprise of Pisa.” He came with few men and less money in which he figured for all practical purposes as [a mercenary] of the League” He rocked up in Genoa, where he was supplied with 6 galleys and some Genoese ships carrying artillery and sailed from there to La Spezia, from which his army marched to Pisa, arriving in October. Honestly, it sounds like a pretty typical German holiday, descending en masse to the late summer Italian sunshine, enjoying a walk through the hills admiring the villages of Cinque Terre and ending up in Tuscany. Maximilian sent threatening messages to Florence, demanding that they end their friendship with France. On the 24th of October, Luca Landucci wrote in his diary from Florence, “We heard that the emperor had reached Pisa, and that he had sent letters here, wishing us to join the League; otherwise he would come against us, and would attack Livorno and all our territory, and put everyone to the sword.” Those are some threatening words, but Florence was determined to resist.

So in late October, Maximilian appeared before the Florentine stronghold of Livorno, which was Florence’s only sea port, and put it to siege. The ships supplied to him by Venice and Genoa blockaded the harbour. Inside Florence, the worried populace flocked to hear Friar Girolamo Savanarola preach. To again quote Von Ranke, “they came in such numbers to hear Savonarola’s sermons, that in the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore, in spite of its great size, galleries had to be built at the entrance, opposite the pulpit, as in a theater. The fasts were most strictly observed. The games that the friar condemned were abandoned; and, in view of the approaching war, they awaited the arrival of the fleet which Charles VIII was fitting out in Marseilles.” The people of Florence, perhaps wary of relying solely on the French, also invoked the help of the Virgin Mary, calling for a special relic, the tabernacle of Nostra Donna di Santa Maria Impruneta, to be brought to Florence.

And then, lo and behold, a miracle happened. To again quote from Luca Landucci, writing in his diary in the city, “October 30: when it [the tabernacle] reached Florence, news came from Livorno that twelve ships of corn had arrived there, but it was in reality the fleet of the King of France, and the Livornese went out and routed the camp of the emperor and the Pisans, and slew about 40 men, and captured their artillery. It was the work of God, in return for our devout worship of Our Lady.” As it turns out, a powerful storm had whipped through the area which had wreaked havoc upon Maximilian’s fleet. Landucci continues “November 17: We heard that the fleet of the Venetians and the Genoese had gone down in the harbour of Livorno, and that many men were drowned. The people of Livorno won much treasure. And there was amongst the fleet a certain ship of corn which they had captured from us, and we now regained. There was also a vessel prepared for the emperor, with all his personal belongings and silver plate on board (he had not gone on shore long when the mishap occurred), which was there at Livorno to help the Pisans to besiege it. They consequently raised their camp, and the emperor lost his ship, having almost lost his life too.” At this point, Maximilian basically dropped his bundle, said “this is too hard” and departed, heading back unhappily towards Germany.

In her book The Italian Wars, Christine Shaw sums up Maximilian’s entire Pisan fiasco when she writes “Highsounding claims to authority as emperor, backed by inadequate forces and compromised by lack of funds, were what Italians had come to expect of Imperial interventions in Italy, to which Maximilian added his characteristic touch of sudden and unexplained withdrawal.” Having learned a lot about Maximilian ourselves throughout the course of this podcast, I think we can all agree that this is a very apt description of the man.

However it would be wrong of us to say that the whole event left no lasting consequences. Especially for one young man! Apparently when he was visiting Ludovico in Italy, Maximilian took a really strong liking towards his two young sens, especially his eldest, Ercole. He liked almost everything about him. Everything that is, except for his name, Ercole. Perhaps he was worried about Ercole’s long term prospects in life, being named Ercole. It sounds like food poisoning in middle school. So Maximilian asked Ludovico whether or not Ercole could be renamed… after himself. From then on, little Ercole Sforza was known as Massimiliano, which we can all agree is a much more powerful name.

Things didn’t work out quite as well for Girolamo Savonarola, the radical friar who had taken power in Florence. Within a few years, the divisions within that city, combined with his extreme moralising and verbal attacks he made on the Church and the Pope, led to him being excommunicated. In May 1498, he and two other Friars were publicly hanged and their bodies burned in Florence’s main square. There’s going to be a lot more like that happening in the next two hundred years that this podcast has to cover, so get used to it.

Unrest continues through Guelders

As nice as it was to be in Italy, it’s time for this podcast to head back to the more familiar swampy delta surroundings of our beloved Low Countries.

To orient ourselves geographically again, Guelders lies to the east of Holland and Utrecht, and to the north and east of Brabant, right near Germany. It’s worth noting, yet again that Guelders was somewhat strange in that it wasn’t one contiguous area of land, but rather sliced up into four quarters by the large rivers which flowed from Germany and France on their gravity inspired journey down to the sea. The “Upper Quarter”, the part which was upstream along the Meuse river, was south of the other three, separated from them by a piece of the Dutchy of Cleves-Berg. The Upper Quarter was bordered on its south by the Duchy of Julich. If you remember back to episode 47, we mentioned that Maximilian had made alliances with the Dukes of Julich and Cleves, as he sought to dislodge the Guelderian prince, Charles of Egmont, from the ducal throne. In the contest between Maximilian and Charles II of Egmont, the people of Guelders were now both surrounded and intersected by enemies.

The issue of who exactly got to hold the title of Duke of Guelders was put before the ever hilariously named Diet of Worms in 1495 and the Reichskammergericht - the imperial court of Maximilian, in 1496. Neither was able to resolve the matter. Maximilian’s Italian job gave Charles a fair bit of breathing time, meaning he did not need to immediately worry about having the Emperor come and lay the smack down on him and Guelders. Instead, Charles of Egmont mostly had to deal with small-scale raids into his lands by the German mercenary troops who had been brought into the Low Countries by Albert of Saxony, which we talked about in our previous episode on Frisia. Furthermore, he also had to deal with problems posed by enemies within. The Gueldarian nobility was not a unified front, with some of the Guelders nobility having pledged their loyalty to the Habsburgs. This saw a bunch of conflicts arise in the years spanning the end of the 15th and beginning of the 16th centuries.

In 1495, a group of troops loyal to the Habsburgs caused havoc throughout the areas of Bommelerwaard and Tielerwaard, which lie on either side of the Waal river. They had been able to get access to two small castles, one called Rossem, controlled by Johan van Rossem, and the other called Echteld, controlled by Otto van Wijhe. The Habsburg-loyal troops were able to use Rossem and Echteld as bases from which to plunder the surrounding areas. This being a major problem for Charles of Egmont, it also compounded other ongoing issues that he already had in the areas. In late 1494 he had imposed an unpopular tax on beer in Bommelerwaard, which lies between the Maas and Waal rivers. The residents of Driel, a town in the district close by to Rossem, aided by servants of van Rossem, made known their displeasure at this tax by burning, looting, and beating several officials to death. By July, 1495, Charles was able to subdue Driel and brought Johan van Rossem back under command, having him pledge his loyalty to Charles and to swear to always keep his castle open for him.

Meanwhile north in Tielerwaard, which lies between the Waal and the Linge rivers, Charles of Egmont had also been having problems with the Lord of Echteld, Otto van Wijhe, for a couple of years. Otto van Wijhe imposed a fine on a man loyal to Charles of Egmont called Berend van Wees for not properly maintaining a dike along the Waal river. Van Wees had disputed the fine and so Otto van Wijhe had been obliged to appear at a courthouse in a place called Kesteren to settle the dispute. Berend van Wees and a group of men busted into the courthouse, kidnapped Otto van Wijhe and took him to Wageningen, where he was brutally tortured. In the meantime, Charles of Egmont went to Otto van Wijhe’s castle at Echteld and filled in the moat before setting fire to it. After Otto van Wijhe was able to buy back his freedom, he went back to his partially destroyed castle and opened up the remains of it to Burgundian troops, putting him back on Charles’ naughty list. So at the same time as he was subduing Rossem, Charles also brought force down on Otto van Wijhe and forced him to submit, pledging to always keep Echteld open for him. Otto van Wijhe was allowed to remain at Echteld, but only held it as a loan from Charles van Egmont, rather than independently from him.

Throughout the next few years there were similar stories across Guelders. Another of the Guelders’ nobility who sided with the Habsburgs was Charles of Egmont's second cousin, Frederik of Egmont, Lord of IJsselstein. In 1496/7, Frederik led a campaign through the Tielerwaard, plundering and setting fire wherever he went. During these campaigns, Charles of Egmont managed to capture one of Frederik’s castles at Leerdam, though it was quickly recaptured, being partially destroyed in the process. Albert of Saxony’s German mercenary troops also wreaked havoc across Guelders. In 1497 his troops were able to capture the castle of Batenburg. So Charles of Egmont might not have been dealing with a full scale invasion from Maximilian, but the instability of the situation which had come to define his life was causing him a lot of headaches all the while, as different nobles, cities and towns slipped into the Habsburg cause.

But all the fighting comes at a cost

All the fighting came at a cost which meant that, by the second half of the 1490s, Charles of Egmont was running low on cash. In June, 1497, at Arnhem, there was a landdag, a meeting of the States of Guelders. There, Charles made his case for an extra injection of cash so that he could hire 200 knights and 500 foot soldiers for the defence of Tielerwaard and Bommelerwaard. The States were reluctant to do this, given that this was not the first time that Charles had come cap in hand asking them for more money in the last few years, a practice that we should, by now, recognise as a staple action of the ruling noble elite in these times. The noble elite held power and influence, but urban centres held wealth. Eventually, the states of Guelders agreed to put up some coin, but under strict conditions. The money would be collected at the capital of each Quarter of Guelders, where it would be put under the supervision of deputies who would make sure that it was not used for any purpose other than the provision of these troops. Also, no other taxes would be levied until this money had been collected.

The Guelders unrest also stifled growth, having a deleterious effect on trade in the area. Remember what we said about Guelders having all of these major rivers running through it? Well it’s pretty hard to move goods up and down rivers when there are angry men with swords plundering, burning and looting along their banks. As we saw in Episode 52, Draining the Swamp Part 2, the town of Dordrecht, in southern Holland, enjoyed the staple right to first sell at market any product on a ship passing by it along the rivers. Dordrecht’s entire economy basically relied on it being able to enforce this right and, as we saw in that episode, they would vigorously and jealously do so, with violence if need be. So it was that, on May 10 1497, Charles of Egmont signed and sealed a neutrality agreement with the town of Dordrecht to ensure the free movement of goods along the rivers. The agreement stipulated that the towns of Poederooijen, Leerdam and Zaltbommel, promised not to damage any ships passing by them. It’s rather interesting to see that despite Maximilian’s wishes to crush Charles of Egmont and bring Guelders into his domain, Maximilian’s subjects in Holland were happy to negotiate with Maximilian’s enemy, given the economic imperative to do so.

Funnily enough, it was not just Maximilian’s subjects who were willing to negotiate with Charles of Egmont, but also his own son, Philip the Handsome. As we have noted time and time again, Philip the Handsome was surrounded by officials in the Low Countries who were more inclined towards peace with France. One of Charles of Egmont’s biggest supporters was, of course, the King of France, Charles VIII. As we have also noted several times, when he took over rule in the Low Countries, in late 1494, Philip the Handsome was torn between the interests of his advisors in keeping peace with France and Guelders and with those of his father Maximilian, who had the opposite inclination. Philip had to walk a fine line. In December 1497, Philip was apparently involved in negotiations between himself, the Duke of Cleves and the Duke of Julich, about how they could divide Guelders up between them. Charles of Egmont sent out ambassadors to Cleves and Julich to try and negotiate a treaty with them to end hostilities, but this they rejected. It must have been quite a shock to them, then, when on December 22, 1497, a treaty of indeterminate length was concluded between Philip the Handsome and Charles of Egmont. The treaty detailed how trade would be allowed to flow between their respective lands, ensured that there would not be any more hostilities with the parts of the Guelders nobility who supported Maximilian’s claim to the ducal throne, and also returned lands to the Lords of Egmont and IJsselstein which Charles of Egmont had captured during the fighting. If either side wanted to end this treaty they could, but they promised that there would be a period of six months after doing so before fighting would begin again. In this treaty, Charles of Egmont was given the title of vorst, meaning prince, rather than hertog, meaning duke, so as to not get involved with answering that tricky question at the centre of all this.

Julich, Cleves and Maximilian go to war against Charles of Egmont for Guelders

In early 1498 Maximilian had become bored with his Italian exploits and was once more ready to push his house’s claims to the Duchy of Guelders and to back that up with military force. Negotiations were held in Dusseldorf, between representatives of Maximilian, the Duke of Cleves and the Duke of Julich. This resulted in a treaty agreed on April 30, 1498, in which they agreed that all three of them would attack Guelders at the same time and not stop until they had brought it under their control. It then stipulated exactly how they were going to divide the lands up between them. This was all ratified in writing by Maximilian at Freiburg on June 19, 1498. Interestingly, Maximilian actually addressed the issue of “who is the Duke of Guelders?” in this document. By this point, he was as good as Emperor and had left the ruling of the Low Countries to his son Philip, who had taken on the title of Archduke. This meant that it was actually Philip who had a claim to the Duchy of Guelders, not Maximilian. But remember, Philip had signed a peace treaty with Charles just six months earlier! In the Treaty of Freiburg, Maximilian begins by saying that he is acting on behalf of himself and Philip, the Archduke, but in the actual signing and sealing of the document, only Maximilian’s name and stamp is there, but not Philip’s.

The other big player we should not forget in all of this was, of course, the King of France. When the negotiations between Maximilian, Cleves and Julich were taking place at Dusseldorf in April, 1498, the French King Charles VIII made his ill-fortuned visit to a tennis match which resulted in him banging his head on a door frame and dying. After his death, his cousin Louis of Orleans became King Louis XII. As well as rapidly making plans to rid himself of his lame wife Joan - see episode 54 - Louis XII wanted to follow the trend of European rulers at this time and go and insert himself firmly into Italy by asserting his own claim to the Duchy of Milan. It was the old reversion to an Italian insertion assertion. If he was going to do that, though, he wanted to make sure he wouldn’t be asked to spend military resources on protecting Guelders. As such, Louis actually sent emissaries to Julich and Cleves in May to see if he couldn’t act as an arbitrator in the conflict between them Guelders. These diplomatic forays were, however, rebuffed. Louis XII had more success with Philip the Handsome. On August 2, 1498, just a few weeks after his father had signed the Treaty of Freiburg, Philip the Handsome and Louis XII agreed to the Treaty of Paris. In this peace agreement, Philip pledged to the contrary of his father’s Freiburg treaty, promising that he would step back from his claims to Burgundy… and to Guelders! This all threw a spanner in the works for Maximilian, who was about to wage a war on Guelders, for Guelders, on Philip’s behalf.

Even without Philip’s help, the agreed upon war against Guelders began in August, 1498, when the Duke of Julich was able to attack and occupy the city of Erkelenz in the southern, Upper Quarter. They were also able to make a few more gains in that area, such as occupying a castle at Echt, and the towns of Stralen and Nieuwstad. This was, however, pretty much the only real success which the alliance against Guelders was going to make. The multi-pronged attack, which in theory sounded like a great idea, actually meant that each of the prongs was more interested in succeeding in the area which had been promised to it, rather than working together. As such, the Duke of Julich wanted to attack Roermond, the Duke of Cleves wanted to attack Doetinchem, the Lord of IJsselstein wanted to attack Tiel, whilst Albert of Saxony, who was putting together the military plans for Maximilian, wanted to attack Arnhem. After the successes in the Upper-Quarter, the rest of Guelders made rapid plans for their defence, giving out money to get troops and ensuring that there were enough grain supplies in their cities to withstand a potential siege. Charles of Egmont was also able to quickly win back the castle at Echt and the town of Stralen. Maximilian, meanwhile, in his usual fashion, rocked up in the Upper-Quarter of Guelders only in October, two months later than agreed. He also didn’t bring with him much of an army and not enough artillery. The town of Venlo was able to withstand the attack. Then, in December, Maximilian decided to head back to Germany, once again doing what he did best and dropping the bundle. On January 26, 1499, Maximilian told a meeting of the States General that “if it had not been for the great haste with which we had marched to Italy to break up the enterprises that the aforementioned King of France had against us, and also for other very important matters that concerned us much more than the fact that the land of Guelders even existed, we would have once again subjected the aforementioned land to our obedience and will” Those are the kind of weak sauce words you might expect to hear from the current coach of the England cricket team.

Things were made much more difficult for the other two dukes involved in this war when the French king’s intervention arrived in the form of boots on the ground. A quick glance at a map will confirm that no French troops were getting to Guelders without going through the Burgundian-cum-Habsburg lands. Louis XII put it to Philip that he should allow for this and Philip, aux croit-conseil, astonishingly but predictably agreed. This meant that French troops marched through Philip’s lands to the aid of the duke that his father was fighting on his behalf. With the arrival of French troops, the allied attack on Guelders lost its steam and the Duke of Julich quickly departed the scene. The Duke of Cleves maintained his attack on Doetinchem, but he too was forced to give up when Charles began leading bloody raids into Clevian territory, taking prisoners and stealing cattle.

The war was brought to a close with the signing of the Treaty of Harkenbosch on June 20, 1499. In this agreement, the Dukes of Guelders, Cleves and Julich agreed to a truce and that they would accept the French King Louis XII’s mediation in their differences until May 31, 1500. If any of them broke it, they would be subjected to a gigantic fine from the French King. It’s pretty remarkable that Louis XII, the King of France, was settling a war between three princes who were, in theory, part of the Empire. As historian Jules Struick put it “by the end of 1499, the balance had tipped in Charles of Guelders’ favour. Not only had he successfully passed the first test of his strength, but his ally, the King of France, had been able to expand his influence over the Lower Rhine princes.”

French King Louis XII intervenes

With the intervention of the new French king, relative calm settled between Guelders, Julich and Cleves in the middle of 1499. In August of that year Charles travelled with an entourage to France to undergo some of the mediation that had been agreed to. Safe passage for Charles of Egmont and his men was agreed by the bishop of Liege and Philip the Handsome to travel through their lands to get to France. In Orleans, Charles of Egmont met personally with the Duke of Julich to settle their disagreement. In these negotiations, the Duke of Julich agreed to hand the town of Erkelenz, which he had captured in the recent war, back to Charles of Egmont, whilst Charles agreed to no longer lay claim to the Duchy of Julich, which was something he had been doing for reasons we have happily chosen not to get into.

Another important piece of business which Charles of Egmont settled whilst in France was securing the release of Bernard van Meurs from captivity. Keen listeners will recognise the name, as we have discussed his being held hostage a couple of times already in various of our podcasts, such as in the bonus episode we made about Comics in the Netherlands, plus in Episode 46, the Treaty of Senlis. Charles of Egmont had been fighting for Maximilian against France when he was captured at the Battle of Béthune in 1488 and held for ransom. He was released in 1492 when the Count of Meurs, Vincent, was able to collect half the money being asked for the ransom. The other half was paid by substituting his grandson Bernard van Meurs in for Charles of Egmont. Poor old Bernard probably assumed this would be a quick and rewarding assignment but, instead, he languished in jail for years waiting for Charles to free him. Bernard van Meurs accidentally created the first comic strip in Dutch history with the illustrated letters he wrote asking for the money to be paid. On June 13, 1500, some eight years after having entered captivity to free Charles of Egmont, Bernard van Meurs was released. In August of that year, Charles returned with him to Guelders and the two were joyfully greeted by the citizens of Arnh em and Nijmegen. In Nijmegen, Charles was gifted two barrels of wine and two fattened oxen, while Bernard van Meurs was given a horse. Thanks for being my proxy in jail for 8 years, here’s a horse.

Throughout this time there were also considerations being made about how the whole Guelders issue could be solved diplomatically. This, of course, meant trying to figure out if there was any way that Charles of Egmont could be wedded into the Habsburg family. There was a suggestion of perhaps marrying Charles of Egmont to Philip the Handsome’s daughter Eleanor, thereby making Guelders a sub-fief of the Habsburg domains. As you can imagine, Charles of Egmont wasn’t particularly keen on this idea, not least because Eleanor was two years old at this point. He was more interested in the idea of marrying, you’ll never guess, Margaret of Austria. Although nothing would ever come of these plans, it does at least show a willingness on the side of the Habsburgs to actually treat Charles of Egmont as an independent prince, rather than as just a rebellious subject.

One thing which we have not yet mentioned is the status of the war between Guelders and Cleves. This was a bit more complicated than the one between Guelders and Julich, because there were several little parts of Cleves which existed within Guelders as enclaves and vice versa. Cleves had actually only agreed to the Treaty of Orleans a little bit later than the others and there were ongoing tensions between Cleves and Guelders. In March, 1501, a six months truce was agreed between the two sides in which trade could resume peacefully. This peace treaty was later extended for another six months with a bit of help from the King of France, once again, but this time with the rather odd stipulation that both sides would be called to France within three months to discuss further arrangements. If the call to France didn’t happen, then the peace would come to an end on January 1, 1502. As such, when Louis XII never actually did what he was supposed to do, the peace between Guelders and Cleves ended on a technicality on that date.

Charles of Egmont attacks Huissen

So while the Clevians sat on their hands, somewhat, Charles of Egmont and the major cities of Guelders had readied themselves for the resumption of hostilities. During the couple of years of relative peace, Charles had been solidifying domestic alliances and by the time the truce came to an end, Gueldarian forces were gathering on the border with Cleves, including 150 horsemen from each of Arnhem, Nijmegen and Zutphen, much to the consternation of the administrators of Cleves.

Charles of Egmont went on the offensive, marshalling troops along the border with Cleves, set on taking the town of Huissen which, like other such districts as Liemers and Malburgen, was owned by the Count of Cleves but sat within Gueldarian territory. This weird status rancoured with Egmont for practical reasons, sitting as Huissen did on the banks of the lower Rhine, thus granting an important strategic position to the enemy. Clearing the Clevians out of Huissen would also be a boon for the further commercial prosperity of the Gueldarian towns of Nijmegen and Arnhem. As it was, Huissen was able to charge tolls that they would rather not pay.

Of course, the people of Cleves noticed the martial activity over the border, but Charles actively sought to temper their fears, insisting that he had no military intentions towards any Clevian enclaves within Guelders. He also obfuscated matters somewhat, highlighting a decree he had instated and promulgated in his lands, stating that there would be severe punishment to anyone from Guelders who harmed or damaged anyone from Cleves. It was also around this time that Charles of Egmont made sure there wouldn’t be any nasty surprises coming at him from the direction of Philip the Handsome, agreeing on May 30, 1502 to continue the peace which they had made in December, 1497, this time also including the Lord of IJsselstein in the treaty. So it was that at the end of May, Charles of Egmont was ready to once again go on the offensive against Cleves.

On the 25th of May, Charles’ troops marched out of Guelders, deceptively in the direction of the castle of Anholt with the pretense of Charles needing to punish a vassal (and cousin) who had become his enemy. The real target was, however, Huissen. On the 29th, they came storming towards Huissen in a surprise attack on the town’s gates. Well it was meant to be a surprise attack but they had, it seems, been seen and the town’s gates had already been shut. On the 7th of June they made another charge, which also failed, and everybody settled in for a siege.

Unfortunately for Guelders, however, when their troops had been spotted on the march, there had been time for Huissen to be supplied with food, weapons and some troops by another town on the Rhine belonging to Cleves, Emmerich. As it became clearer that a siege was on the cards, it was Emmerich, along with the next couple of towns up the river, Rees and Wezel, whom Huissen would need to rely on if they were not to be starved out by Charles of Egmont. These three towns assembled troops in Emmerich, where they waited for other Clevian troops to arrive so, together, they could go and give the Gueldarians what-for. This allied force, led by the Duke of Cleves John II, was composed mainly of several thousand angry Cleves peasants and burghers, with only about 80 professional knights and soldiers, who were kept back and apart from the main force. They set off marching down the Rhine towards Huissen, where they camped on the bank opposite the Gueldarian troops, under the gaze of Charles of Egmont.

It is generally agreed that Charles of Egmont underestimated them and in the night between June 25 and 26, 1502, decided to lead his troops off on what was supposed to be another surprise attack. Under the cover of darkness he and about 3000 of his troops crossed the river to raid the enemy camp. They were, however, once again given the leopard-treatment, and somebody spotted them as they did so. As a result they were met with a far more numerous, well rounded and organised defence than what they had anticipated. The Gueldarians were immediately put on the back foot. When the force of professional soldiers, who had been held - and, indeed, camped apart from the main Clevian force - joined the fray, it turned into a rout and the Gueldarians were forced to flee. They left numerous artillery and cannons behind, as well as around 1000 dead and wounded.

From the aftermath of this battle emerges the story that Charles of Egmont was actually captured by Clevian soldiers in the rout but managed to escape with the help of one of his trawanten, the term for members of his bodyguard. The word in modern Dutch has negative connotations, meaning a scoundrel or even a violent gangster. From the late middle ages until the 18th century, however, trawant or truwant meant a subordinate protector of a high-ranking person. This trawant of Charles, an African Moor called Jacob, is said to have put the prince of Guelders onto a little boat and rowed him back across the river where he could safely lick his metaphorical and perhaps literal wounds. It is really hard to find good historical evidence to verify this story but it’s an interesting detail nonetheless.

So that’s where we are going to leave this episode. Charles of Egmont has managed to escape with his life after suffering this dramatic defeat at the failed siege of Huissen. Unfortunately for him, however, this was just the beginning of a reversal of fortune for him and Guelders. Maximilian’s resolve would be hardened in his attempts to conquer Guelders and his son, Philip the Handsome, would soon also be convinced to join in his father’s efforts to crush Guelders and bring Charles of Egmont to his knees. But all of that is for future episodes of History of the Netherlands…

Sources used

The Italian Wars 1494-1559 by Christine Shaw

Milan Under the Sforza by Cecilia M. Ady

A Florentine Diary from 1450 to 1516 by Luca Landucci

History of the Latin and Teutonic Nations by Leopold von Ranke

Gedenkwaardigheden uit de Geschiedenis van Gelderland by I. A. Nijhoff

“Otto van Wijhe versus Karel van Gelre” in Stamboom Dossier Karel van Gelre (https://www.genealogie-rene-martens.nl/files/2514/6321/4848/Stamboom_dossier_Karel_van_Egmont_1467_1.4_160514.pdf)

De Betuwe by R.F.P. de Beaufot, Herma M. van den Berg

“Frederik van Egmond (1440-1521)” by E. J. C. de Veer (https://historischeverenigingleerdam.nl/historische-artikelen/frederik-van-egmond-1440-1521/)

Gelre en Habsburg by J. E. A. L. Struick

“Beleg en Ontzet van Huissen” by Jan Wannet (https://mijngelderland.nl/inhoud/specials/een-wagen-vol-verhalen/beleg-en-ontzet-van-huissen)

“Het Beleg en Ontzet historisch bekeken” by Louis Muller (https://www.gildenhuissen.nl/het-beleg-en-ontzet-historisch-bekeken/)