Episode 55: Full-on Frisian Foray: Freedom & Foreign Frenemies in the 15th Century

Over the fifty-four episodes of this podcast so far, we have often found ourselves fixated on familiar fields of sphagnum, or ferocious fights in far flung foreign fields, but frequently we’ve failed to focus on the fortunes of the fierce and frisky - fabled to be free - Frisians. Folly! Fear not Frieslanders, for now it is your time to shine. In this episode, we are going to delve into Frisian Law and Frisian Freedom in the 15th century: We will look at how they developed up until the end of the 15th century; examples of how Frisian Law impacted peoples’ lives; how local governing structures specific to Frisia changed in the 15th century and how in 1498 these new conditions allowed Frisian Freedom to finally be stamped out by the very Emperor who was supposed to uphold it.

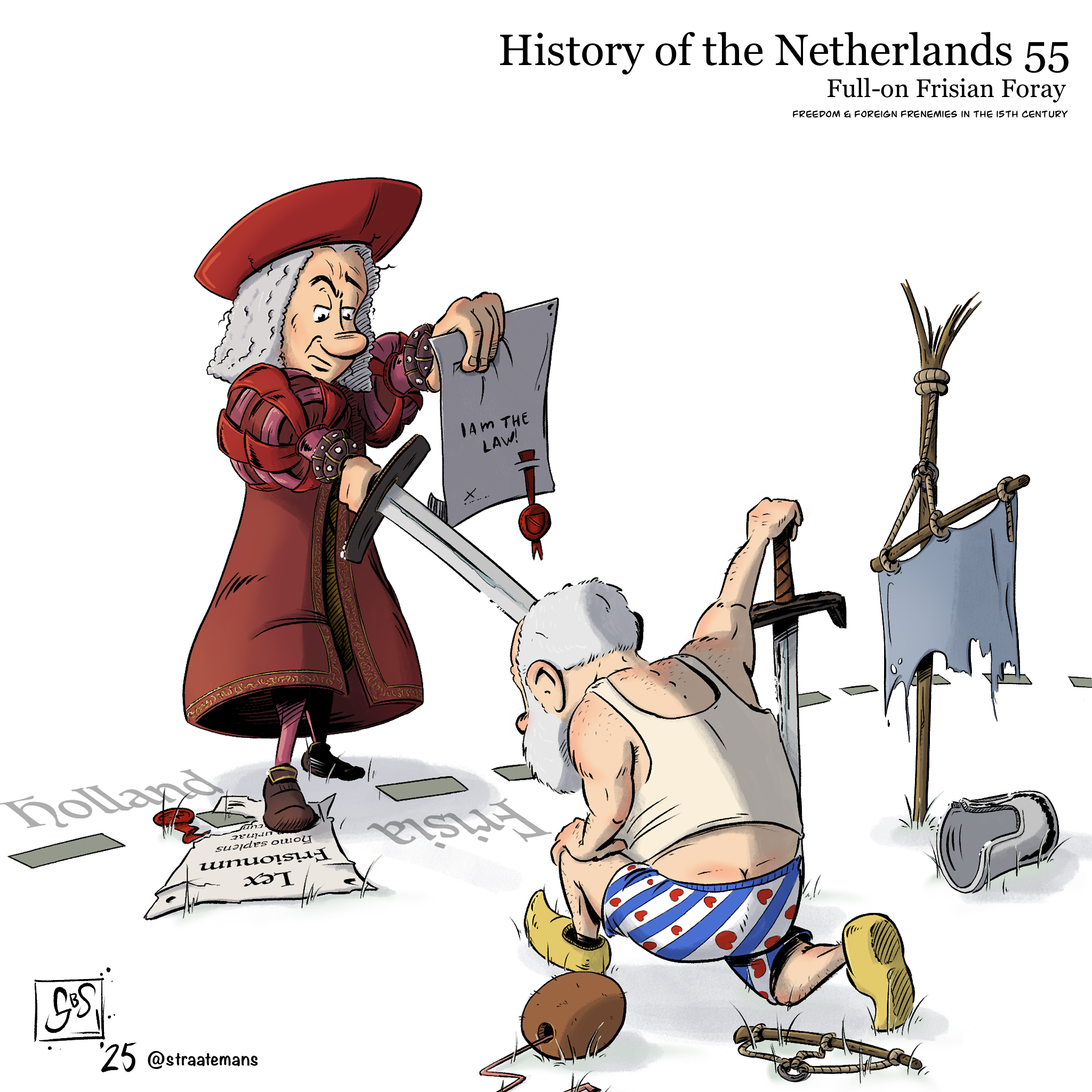

“Full-on Frisian Foray” episode artwork by Steven Straatemans

Recap on Friesland and its status

If you, like us, have also frequently forgotten about Friesland, then join us as we remind ourselves of what it is, both currently and historically. Today, Friesland is a province in the north of the Netherlands, which on its north and western edge borders the Waddenzee and the IJsselmeer (formerly called the Zuiderzee - The Southern Sea); on the south it borders a modern province called Flevoland (which, as it happens, was also formerly the Zuiderzee and, some might say, should have probably stayed that way). On its east, Friesland borders the provinces of Drenthe and Groningen. But modern Friesland is only a small part of ancient Frisia, which extended north from today’s Flanders up the coast of the Waddenzee into northern Germany. If you want a recap on that, go and listen to Episode 3. Sufficient for this episode is that from the 1300s Frisian identity was indelibly cast in the frame of freedom. Freedom from a prince; freedom from servitude; freedom to appoint their own magistrates and freedom from taxes.

We spoke about this in Episode 15, but in short, the idea of Frisian Freedom originated from rights and liberties purportedly granted to the Frisians by the great Frankish emperor Charles (AKA Charlemagne). Sometime between 1297-1319 the Frisians produced a charter that is sometimes known as the Karelsprivilege, or Charles' privilege, which we are going to call Chuck’s Charter. According to the Frisians, Charlemagne had granted their ancestors this charter around 500 years earlier, after he had subjugated them in the 780s. Some sources cite the reason as being because they had given outstanding military assistance in his military campaigns, even capturing Rome on his behalf. One section of Chuck’s Charter reads: ‘And moreover, by royal authority, we [Charlemagne] have granted that they [the Frisians] shall remain free, with all their progeny, born and yet to be born, in perpetuity, and be fully absolved from personal servitude. We also decree that no one will rule them, except if this happens by their own volition or consent.’ Those are some high-minded and definitive declarations of freedom which most historians agree was a forgery, constructed hundreds of years after Charlemagne was dead. Despite this, such an idealised official liberty was a point of difference between the Frisians and other peoples of the Empire.

After having conquered them, Charlemagne compiled the local rules of the Frisians into a legal framework which was called Lex Frisonium, which applied to pretty much the whole coastal region running from Flanders up to Saxony. This was mainly conveyed orally until probably the 11th century, when it began to be written down in Old Frisian. It was not the only collection of laws, however, as a whole complex array of them continued to be developed and implemented across the different regions of Frisia. However, according to legal history Han Nijdam,

“The Lex Frisionum is the first historical source to describe the three Frisian core regions:

1. West Frisia: between the rivers Sincfal (Zwin) and Vlie (i.e. the present- day provinces of Zealand, South- and North-Holland in the Netherlands).

2. Central Frisia: between the rivers Lauwers and Vlie (i.e. the present-day province of Fryslân / Friesland in the Netherlands);

3. East Frisia: between the rivers Lauwers and Weser (i.e. the present-day provinces of Groningen in the Netherlands and the region Ost-Friesland in Germany).”

Despite having fraudulently created Chuck’s Charter for their own benefit, the Frisians were able to get later emperors to grant charters of their own. In 1248 the Count of Holland and King of the Romans, Willem II granted them "all the rights, liberties and privileges conceded to all Frisians by the emperor Charlemagne" as reward for helping him capture the imperial coronation city of Aachen. Nearly two centuries later, in 1417, Emperor Sigismund granted them his own charter and in 1479 Frederick III even drafted something similar, but died before it could be put into law. Finally, in 1493, Maximilian would also grant his own charter, which ratified all of those that preceded it. “We reaffirm, with our royal authority, all the privileges of Kings William and Sigismund, of Emperor Frederick the Third our most honoured progenitor, of all other Emperors and Roman Kings, our predecessors”. The thing about Maximilian though, is that he was never one to let something like a promise get in the way of doing what was best for him and his. He would use terms included in Chuck’s Charter, notably reference to a government office called Potestas, meaning essentially a governor, to bring an end to 700 years of Frisian Freedom a few years after granting his charter. We will get to that later!

Threat by foreign princes

Historians have long enjoyed debating about what freedom meant to the Frisians at different times in history. One of the core tenets, however, which most agree on was that the Frisians rejected the idea of having a foreign prince, or any prince or lord, for that matter, take control of their sovereignty. The original Frisian counties that had been established by the early imperial system that developed out of Charlemagne’s empire had, by the 14th century, dissolved into smaller communal districts known as terrae. The sovereignty of each of these lay with the universitas terrae, “land-communities” which were comprised mainly of land-owners who elected their own local magistrates. They were small, self-governed polities not in obligation to a feudal lord; except, that is, the Emperor, who was never around anyway. People lived in village-level communal structures, where the issues which affected their day-to-day lives were dealt with by people they knew within their community. This was opposed to how so many other people in Europe experienced life, which was to have a Prince or Lord involved in, potentially, every part of their lives, even from a distance.

As the Dukes of Burgundy and then the Habsburgs tightened their grasp on the Low Countries during the 14th and 15th centuries, the Frisians stood by their right to freedom and obligation only to the Emperor. As mentioned earlier, in 1417 they extracted an actual charter from then Emperor Sigismund that stipulated their freedom from princely rule. However it also made them pay him something called the huslotha which was an obligatory tax. The Frisians were not happy about it and from this point on taxation, too, would be a consistent bone of contention when it came to what Frisian Freedom meant.

Around the 1430s, there were several alliances made between the more powerful ranks of Frisians which often cited the need to protect Frisian Freedom from a foreign ruler as a reason for cooperation. Clearly, it was a major reference point for Frisians and a prospect of which they had a right to be wary. As Frisian Medievalist Hans Mol wrote, “As far as the threats from outside were concerned, at the time of Philip the Good and Charles the Bold, the country’s municipalities had to seriously fear a new invasion from Holland several times. They often consulted, negotiated, and no doubt made plans for how a Burgundian invasion should be dealt with, but, in the end, such plans never had to be carried out.”

In “Episode 32: Charles, King of Burgundy” we saw Charles summoning some representatives of Friesland and telling them that they needed to accept him as their rightful sovereign. After a bunch of prevaricating, endless meetings and typical Frisian disunity on the matter, Charles declared war on his Frisian subjects in November, 1470. This war never ended up happening because of Charles’ seemingly endless conflict with the then French king, Louis XI, who shortly thereafter invaded the Somme region. When Charles the Bold resolved his years-long conflict with the French king by dying in 1477 in a muddy ditch, it seemed like the Frisians were off the hook. In that episode we ended our tangent into their part of the story saying “So the Frisians just kept doing their Frisian thing…”

What then, was that Frisian thing?

Context to Frisian Society

A cornerstone of life in Friesland was the system of laws that governed the communal societies, largely built upon the ancient law code mentioned earlier, the Lex Frisionum and multiple other laws, some equally ancient. Since Charlemagne’s subjugation of the Frisians, there had periodically been men appointed as the Count or Duke of Frisia, but they had never been physically present and in control in Frisia itself. As a result the Lex Frisionum was developed on a domestic level, relatively unmolested from afar by generations of foreign, lofty rulers meddling with it. The advent of book printing saw the publication of these laws as a core collection, of which nine copies survive.

A few contextual things about Frisia should be highlighted in regards to Frisian life, freedom and law. Firstly, the people that we are talking about were subject to flooding and mindful of water control, as is always the case when it comes to talking about the Low Countries. The archeological remains of collapsed and drowned medieval settlements which have been found across Frisia testify to the fact that flooding was a near constant threat so, as always with this podcast, we should constantly keep this in the back of our minds. Other major contextual considerations which scholars who seek to understand medieval and early-modern Frisian history need to bear in mind include the establishment of the church, the viking era, and the (future) Protestant Reformation of the 16th and 17th centuries. To start backwards, the ‘as-yet to happen in our podcast narrative’ forthcoming Reformation wreaked absolute havoc with records, chronicles, annals, and much other material that, had it survived, would doubtless have helped us much better understand the era that came before the schism. Alas, like a wave bursting through a dike, the Reformation came and swept away so much before it. And we have all of that to come. Yikes.

Like everywhere in Europe, the establishment of the Christian church and people embedded within its structures were fundamental in putting ink to paper. Historian Dirk Jan Henstra has suggested that one of the Frisian monasteries, Reepsholt, said to be founded on the orders of Charlemagne, assisted in the writing of the oldest known Frisian Laws, called The Seventeen Statutes. This law dates from the 11th century but probably contains material from as far back as Charlemagne. Certainly the first ten of the statues are about aspects of the Frisians’ relationship with Charlemagne and his successors.

A Christian presence began in Frisia in the earliest years of the 8th century and grew in step with the communalism of the middle ages. Christianisation was initiated by missionaries we have spoken about before on this podcast, Willibrord and Boniface. As a process, however, it was enforced by the swords and spears of the Franks. As the Frankish occupation of Frisia unfolded, estates that had been taken by royal forces were provided for the construction of churches. However, the local aristocracy also donated land, presumably as a show of support towards the new regime. Churches, abbeys, monasteries, convents and more churches were built across Frisia and many of them were owned by Frisians. In their essay “Church Foundation and Parish Formation in Frisia in the Tenth and Eleventh Centuries”, Frisian medievalists Gilles de Langen and Hans Mol tell us that “generally, in this period the ownership of the churches stayed with the founders of the churches and with their successors in title. Those who held the titles controlled the appointment of ministers and received a share from the revenues of the church. These revenues were generated both by the estate of the church (through farming) as by the parishioners paying their dues. The term proprietary churches or Eigenkirchen is often used to describe churches of this kind.”

Simultaneously, the episcopal centres of Utrecht and Münster were also establishing a wider reach, as they took over lands and also built more churches. What developed in Frisia was a dual system. While most churches in Frisia were diocesan (meaning they came under the direct control of one of those bishops), there were also these other establishments that did not belong directly to a diocese. Rather, they were monastic, meaning that they belonged to one of a few different abbeys that were essentially the successors of land-owners who had granted land for churches to be built, back when the Franks had come waltzing in.

The growth of the church in Frisia and the complete christianisation of its peoples was not without setbacks. The largest of these was the age of the Vikings, which Frisians were not just exposed to, but literally partook in. To quote Gilles de Langen and Hans Mol again, “the Church in Frisia probably suffered heavily under these Viking attacks. Her material capital consisted mainly of movable property such as reliquaries, liturgical vessels, and books, which were often decorated with precious metals and gems. When these were robbed and priests were assaulted or killed, it was difficult to keep the institution going…we can say that the development of the parish system came to a halt and even witnessed a setback in the course of the ninth century as a result of the Viking raids. We are inclined to think that in and shortly after the Viking period, many Frisians shared the pagan religion of the invaders and temporary new rulers.”

The Viking age ended for Frisia in the 11th century after which Christian missionary work once again flourished, driven by the Bishops of Utrecht and Münster. It was not long before it was universally (pun intended) impacting every life across the Low Countries. Some stories from this period suggest that not everybody in the North had yet bought in. There is a Latin text from the 1020s called The Deeds of the Bishops of Cambrai that perhaps reflects the different levels of commitment to the cause between people in the South and those in the northern reaches of Frisia. The parable tells of a ruler in Frisia publicly expressing doubt about the eucharist and extolling his people to join him at the tavern to drink beer instead of nibbling on the holy wafer. Naturally, as the story goes, he was almost immediately punished by God, and fell dead from his horse.

A strength of the church was that it filled voids in communal spaces. In the second half of the 10th century a ‘parochial infrastructure’ was built which would tap into the resources of humans in the community and, by doing so, fuel the increase of literacy and, therefore, source material. As monasticism recovered and flourished after the end of the Viking era, the network of churches and parishes became stronger and, in bigger towns like Leeuwarden, schools were established by the local church, which taught people to read and write.

In such ways, the church became ever more indelibly intertwined with what was still a communal society. Another of the very oldest Frisian laws is The Synodical Law of Central Frisia, which is traditionally dated to the 11th century but contains elements from both earlier and later than then. The synod would take place annually over a four year cycle, called the circatus and was overseen by men holding ecclesiastical offices. In one of the four years the Bishop of Utrecht himself would preside over it. In the other years, this was done by a dean of the church. Interestingly, the synod states clearly that “The dean shall be free and Frisian and born of free stock and his ordination shall not be nullified and neither shall he have lost his legal status as a consequence of having committed crimes, and he must be the son of a layman.” This exemplifies the decentralised way that the church existed in Frisia, upholding the uniqueness of Freedom that the Frisians had managed to construct for themselves. As a standard, Frisian Freedom was upheld by members of the Frisian clergy as well as everyday people. In the 15th century a series of legends, collectively known as Gesta Dei per Frisios, ‘God's deeds through the Frisians’, became popular around Frisia, as Central Frisia became the last part of the region not to have yet succumbed to external rule. These stories generally all tell of a Frisian origin myth of being enslaved by Danes, freed by Franks and Christianised under God’s blessing, with consistent parallels made between them and the people of Israel. The point is that Frisia became as devoutly Christian as everywhere else in the Low Countries, but the religion and its educational institutes were also utilised to reinforce their communalism and self-generated concept of Freedom.

Free Frisian under Frisian Law

Perhaps one of the best ways we can get an insight into the people who called themselves Frisian and how they saw themselves and the world, is to take a look at some of their conventions which were upheld by Frisian Law. Most of this section of the episode leans on the work done by Han Nijdam, Jan Hallebeek & Hylkje de Jong on Frisian Land Law.

Under Frisian Law, a free Frisian was someone who was born legitimately to a free Frisian man and a free Frisian woman who were legally married. In matters like inheritance and succession, the line of descent was bilateral meaning it followed both the father’s side - known as the ‘swirdsida’ (sword-side) - and the mother’s side - known as the ‘spindelsida’ (spindle-side). Based on the work of medievalist P. N. Noomen and colleagues, however, historians think that this changed somewhat in the later 15th and 16th centuries, towards favouring male descent. A person, male or female, was considered a legal adult at 12 years old, at which age women could also get married and could actually choose their husband. The above mentioned Synodical Law of Central Frisia tells us what a traditional Central Frisian marriage ritual is, in the context of a defendant having to prove the legitimacy of their marital status. Paragraph 62 says:

“If a case is brought before the court concerning an illegitimate marriage and the case is to be tried, the accusation shall be presented thus, that the free Frisian woman came under the guardianship of the free Frisian accompanied by the sounding of horns and the clamour of the neighbours, by lit torches and the singing of friends, that she stepped into his bed as a bride and enjoyed her body with her husband and got up in the morning, went to church, heard mass, honoured the altar, paid an offering to the priest and thus entered into matrimony as a free Frisian and a free Frisian woman ought to. Then seven neighbours as well as the priest who read mass and received the offering and who lead her into the church and the sacristan who tolled the bell shall testify of the marriage. In this way, the legitimacy of the marriage can be defended in court with these nine witnesses, rather than that any Frisian can claim it to be invalid.”

So there you go, if you are looking for wedding ideas, consider Medieval Frisian communal style, where your neighbours make a clamour by… banging saucepans, I guess, and blowing horns, while your mates sing and hold torches up to usher you into bed with your newly betrothed.

A dowry was provided to the woman by her father and she was then also entitled to half of whatever wealth was accumulated in partnership with her husband, called the be in Old Frisian. She was not, however, entitled to whatever wealth or assets he brought into the union so that in the case of his death, she would only receive her dowry and share of the be. To have any look in on her husband’s original inheritance, she (and he) could embark upon another legal path, whereby they agreed that her wealth (dowry and assets) would become a part of the commonly held wealth of the couple and her husband could then name her as one of his heirs meaning that, if he died, she would inherit a third of his wealth.

Being a bilateral system, women had slightly more protection from the law than in many other places. In one of the Frisian Land Laws, The Book of Emperor Rudolf, it says “if a father and a mother beget three children; two sons and one daughter, and if their parents pass away and if the daughter then marries a man without having consulted either of her brothers, the brothers will claim she has lost her share of the inheritance because she entered into the marriage without their consultation. Now her husband says she did not lose her share of the inheritance because of the free choice which was given to her and all women by King Charles and which King Pippin later wrote down. Because they have dominion over their own bodies and limbs and the right to choose a husband. Because of this, the court shall find in favour of the women and against the brothers or the parties shall come to an agreement after consultation and on the advice of wise men. If these wise men cannot come up with a solution, the woman’s rights shall prevail.”

Family was central to Frisian society (as is the case in most) and the direct kin to a person - father, mother, brother, sister, son and daughter - were collectively known as ‘the six hands’. In a legal sense, this was important for issues such as inheritance, succession and also something called the wergild. This was a Frisian version of something that was quite prevalent across Europe in the middle ages and which scholars generally believe was brought with Germanic migrants in the 5th century when they migrated westwards into the river delta. In the event of a murder, the perpetrator could allay the potential for revenge attacks by the victim’s kin by paying them wergild. In Frisian Land Law, Nijdam and the others write: “this was often accompanied by a ritual of swearing peace between the families involved.” Traditionally across Europe this blood-money would be a set price depending on the class of the victim, with a nobleman being worth double a free-man. Nijdam elaborates on this: “In many societies that had invented the institution of wergild, the concept was used to also put a price on not losing a life, but losing a limb. What is the value of a hand that has been cut off, or an eye that has been poked out or is blinded for the rest of the victim’s life?” The kin, or the ‘six hands’ were both the receivers of the Wergild or, if their relative had actually committed the crime, were responsible for raising the wergild on their relatives behalf.

Governance & rise of Haedlingen

People in towns and territories in Frisia were engaged politically in decision making processes, mutually beneficial defense arrangements and resource sharing. Nijdam tells us that “Officially the Frisians were part of the Carolingian realm, but basically they ruled themselves, using their age-old infrastructure of local and supralocal assemblies…to build a grass roots government structure. All freeholders and nobles were eligible for the office of judge-administrator, which rotated every year.” Defense of a local region depended on every fit male between 16 and 60, who was obliged to assemble when called upon. Land-holders were expected to bring gear with them to a fight. The amount of land you owned determined what you had to bring to a fight ranging from a horse and weapon for the largest landholders to a bow and arrow for those with parcels of land below a set amount.

Decision making depended on communal assemblies, known as a thing - which is a definitive harkening back to the pre-Christian ways. The term also makes our ‘Doing their Frisian Thing’ a hilarious double entendre. The Opstalboom was one such annual assembly that we spoke about in Episode 15, which was a pan-Frisian thing to which the different areas sent their representatives. This was often a locally elected magistrate known originally as asega, but eventually as either redjever or grietman, depending where in Frisia you were. Later, legal professionals would be known as Asega. Hans Mol tells us of the regularly held assemblies that “These colleges met regularly for matters that concerned the entire land, such as alliances and interpretation issues, but also to deal with higher court cases. They were responsible for the handling of crimes and misconduct above a certain penalty amount. Together, they also acted as a court of appeal. In the sources we find their competence described as the hagista riocht or the highest court. It may be assumed that they also dealt with military matters at the highest level.”

Interestingly, in terms of government structure, Chuck’s Charter, while a forgery, includes the premise of there being elected consuls, similar to the Roman Republican system as well as another, even higher office, called the potestas. This latter would be like a general, single governor of all of Frisia.

“We [Charlemagne] also decree that these consuls, according to the custom of the Romans, shall annually elect a suitable and righteous person, under whose government, rule and power the whole of Friesland shall be disposed and subjected [and] whom they shall be obliged to obey, in all and in every respect, as their true lord, within the time limit allotted him by them, which person ought to be called the potestas of Friesland.”

As historian and Frisian medievalist Oeberle Vries points out, this is a bit of a weird surprise, along with the fact that directly after that paragraph the charter also gives the provision for this governing potestas to be able to grant knighthood to a wealthy consul. Historians know that the charter was created sometime around 1300, at which point there was no such role as potestas in Frisia but they included it nonetheless. Vries reasons that “it could be argued that in the essentially leaderless Frisian society, where feuds among the leading families were the order of the day, there was a real need for a single individual to whom executive power could be transferred for a limited term. Something similar was felt in the towns in the western part of Friesland, some of which decided to elect a suitable person, mostly a haedling, to serve as president of the city council and also as chief executive magistrate and military leader. This urban officeholder was called an alderman, however, and not a potestas. The first mention of such an urban alderman dates from 1298 or 1299. Apparently the potestas was meant to be a kind of super-alderman for the whole of Friesland.”

Vries goes on to argue that the term was an inheritance of an Italian office podestà, found originally in the cities of Bologna, Verona, Ferrara and Siena around the mid 12th century but which, within a century after that, had “become the prevailing form of government in Italian cities…There is evidence that there was at least some knowledge of this Italian institution in thirteenth-century Friesland, as there are two references to a podestà in the chronicle of Bloemhof Abbey”. He goes on, “the spurious charter of Charlemagne – as we now know – only emerged at a later date. It is much more likely that the idea of having a potestas was brought to Friesland by Frisians who had spent at least some years in an Italian city governed by a podestà. In this regard, there is only one group of individuals that comes into serious consideration: university students. Bologna was an important centre for the study of both Roman law and medicine in the thirteenth century – and it attracted a remarkably large number of students from Friesland. Nearly all of them, 43 in total, matriculated there during a period of only 12 years, from 1290 through to 1301.”

So coming into the 14th and 15th centuries, the idea of a potestas existed in Frisia, even if the actual office did not. Spoiler alert, this is going to become relevant towards the end of this episode so it’s worth remembering!

By the late 14th century the power structures across communal Frisia changed tack from communalism, toward an emergence and preponderance of local, powerful men taking ever greater control of the areas around their homesteads. These men are known in Frisian as Haedlingen, in Dutch as hoofdelingen, in German as Häuptlinge and in English as… head-men. Historians of Frisia debate whether they emerged from amongst the wealthiest and most resourced members of the communes - forming what has been called a ‘farmers’ aristocracy’ - or whether they constituted a latent noble-class that had never actually disappeared from Frisia, despite the popular notion of feudalism-free Frisia that suggests otherwise. Paul Noomen is one historian who has solidified this latter assertion, pointing to the heftier Wergild compensation due for certain persons that indicate a traceable line of nobility back to the 8th century. Another historian, Hans Mol agrees, but points out that, even assuming there was an ancient high nobility in Frisia, “Under no circumstances do they seem to have been persons who could establish kinships with, for example, Saxon high noblemen or other territorial magnates. Rather, they seem to have been men to whom the informal leadership of a local community could be attributed on the basis of their origin and prestige.” So although there was a nobility, they were still somewhat disassociated with the nobility of Burgundy or the Empire. The origin and prestige that formed the basis of their leadership relates to land ownership. Being an agricultural and communalistic society, farm-holds were, in the words of Nijdam, “the core unity of Frisian medieval society… from a socio-economic point of view.”

The 15th century haedlingen and their clans were strong political forces in their localities. Their dominance was more severe in East Frisia (the German part), where many long-established communal rights and structures - the appointment of magistrates being an example - were swallowed up by men acting as independent lords over subjects. This led to the outbreak of what is known as the Great Frisian War, fought between feuding families between the years 1413 to 1422. Eventually, large tracts of East Frisia were turned into an imperial county around the middle of the 15th century, with a family called the Cirksenas elevated to the status of counts.

In Central Frisia (the part which corresponds to the modern Dutch province of Friesland) communal norms and structures weren’t swept away as vigorously as in the east. But here, in the regions of Westergo, Oostergo and Zevenwoude local, powerful families still bore heavily on the scene, holding positions of power within the local magistracy and keeping them in the family. A couple of sources give us data about this class of powerful people in Central Frisia. One is a tax list from 1479, by which we see that the largest land holdings were around 100 acres, of which several could be owned by one person or family. Crucially for Friesland, this list also tells us that the number of cows per farm could range from four cows to twenty cows.

The second source is from slightly after the occurrence of Frisian Freedom going up in a ball of Saxon smoke, which in our narrative is going to happen in 1498 (towards the end of this episode), but it is close enough in the timeline to give a pretty accurate idea of how things looked in the lead-up to this. In 1505, so 7 years after Central Frisia got itself a prince, the status of ‘privileged lordship’ was conferred on those who agreed to a new tax that would be paid on every 21st penny. From the records, there are about 60 families, of around 240 members, who took the deal. It is worth pointing out that they were mostly in the older, clay-rich part of Central Frisia. Of this class of haedlingen, Mol writes “this circle of hoofdelingen in Friesland west of the river Lauwers was not a homogenous group in these centuries. There were major and minor, i.e., wealthy and less wealthy, hoofdelingen, and both groups had more and less wealthy branches. For all branches, proper marriage was an important strategy in the competition to maintain and increase honour, power, and prestige. How this stratification was created is difficult to say due to a lack of sources. What is certain, however, is that in the fourteenth century there already existed a permanent group of major principals who had their bases of power in the cities or large villages and whose families owned a few hundred hectares of fertile farmland divided over several dozen tenanted farms. They married one another as much as possible, on a material and culturally equal level, in order to prevent the loss of property and honour by inheritance.”

On their homesteads some haedlingen built stone fortresses, or stins in Frisian. A stins is a long and strong, stone-built stronghold that would be constructed next to the residential farmstead. Effectively, they were quite simple castles, some of which became extended into proper castles, in which the haedling and his clan actually lived. He or she who controlled the stins could consolidate their land-owning power by offering protection to others during times of trouble (of which there were many, what with the nearly two centuries of factional feuding taking place that we will talk about shortly). This generosity was more an act of political expediency, as it would help them be elected to local positions, like that of grietman, who was a judge and administrator of a district. These roles, for which only land-owners were eligible and that were traditionally representative of fabled Frisian Freedom, could then just stay in the same families’ hands.

So if you imagine Frisian society in the early 15th century to be like a human body, at the head were the… haedlingen, while at the butt were the rest of the bumpkins. Okay that was kind of a strained analogy but whatever DINGDINGDING ‘bumpkin’ brings us to this episode’s installment of Bet You Didn’t Know That Was Dutch! The English word ‘bumpkin’, meaning an awkward person from the countryside, is derived from the middle Dutch word ‘bommekijn’, meaning little barrel or little tree. The word entered the English language via, you’ll never guess it, ship building, where a bumpkin (or a boomkin) refers to a short piece of wood which extends from the front or back of a ship which holds a block that sails get attached to. Funnily enough, it was used as an insult in English towards Dutch people, because they were apparently short and dumpy. Well how the tables have turned now, English people, with the Dutch towering over all you little bumpkins. Bumpkin! Bet you didn’t know that was Dutch.

The rise of the haedlingen provided the flames to Frisian internal politics from the 1350s until the late 1490s. During that time there raged an on-going factional conflict between two parties called Vetkopers, “Fat-buyers” & Schieringers, “shearers”. With freemen and powerful haedlingen on both sides, the Schieringers were generally the traditionalists; established old families of wealth, harbouring a greater desire to have closer ties to imperial governance; and the Vetkopers were generally lesser ranked ‘nobility’ allied to common free-hold farmers who were much more into self-government than having more ‘Empire’ around. Like similar factional conflicts we’ve seen in the Low Countries, this is a convoluted dispute to pin down, due to a paucity of sources, as well as the fact that by the 15th century the conflict was so much about identification with one party or another than it was about certain issues. People would often take decisions and actions based on the party alignment of whomever was involved, rather than what was actually good policy or even something that just looked like structured governance. In the words of Frisian medievalist Hans Mol, “...the military events that resulted are poorly documented, making it difficult to trace the principles of their commitment.” So nobody really knows what many of the fights were about, but they were long, intertwined and recurrent, setting the scene for the instability that would let the empire in.

1470s-1498

Hopefully we have adequately set the scene for the final decades of Frisian Freedom to play out. From 1479 until 1498 the on-going internal feuding played right into the Empire’s hands. The 19th century Romantic Dutch writer Jacob van Lennep gives a solid description of the social context of Friesland in the latter half of the 15th century in his “Geschiedenis der Nederlanden”. Van Lennep’s work was not written in a way that would meet the rigours of modern academia. He was writing at a time when the modern Dutch national identity was being shaped and so bits and pieces might fall more into the category of ‘folk legend’ than history. He does tend to mix fact with fiction, but offers juicy details which are hard to resist talking about… so every time we mention Van Lennep, just stick an asterisk next to it in your mind.

Van Lennep states that this was a violent age of raids and xenophobia in Frisia between the two parties, composed of different clans. “Although no feudalism existed in that country, and all the inhabitants could consider themselves free and equal, a certain distinction had naturally arisen between the members of the powerful families… who lived as landowners on their own ditches or stinzen, and the less affluent lords (geërfden), and farmers. The former exercised a right of protection or patronage over the others. Moreover, since the rise of the cities (by these he means places like Leeuwaarden, Stavoren, Dokkum, Franeker, Harlingen, Sneek and Sloten), the proud landowners looked down on the townspeople and their trade. However, this was not the case everywhere: for although the cities, as elsewhere, were governed by government officials, there the government was usually headed by a nobleman, in whose lineage it remained hereditary. Thus, in Franeker, the Sjaardemas, and later the Hottingas, in Sneek, the Harinxmas, and in Bolsward, the Jongemas, held the reins of power.”

Historians agree. Hans Mol, for example, says: “intertwined feuds in [Central Friesland] in the years 1458 – 1464…together became known as the Donia War. These were ephemeral acts of war in which, in addition to looting and destruction, robbery and hostage-taking were the most important means of fighting. These acts served to strengthen the positions of power of the important families of hoofdelingen, in the cities and other strategic points along the main waterways in the southwest corner. However, the existing political-communal structure does not appear to have been fundamentally altered by them.”

Van Lennep adds a little flavour to the story, though, emphasising how deadly it was for a foreigner to be caught in the wrong part of Frisia because, if you were caught, you would be forced to say the following: "raed hird rekt zierrens lyre: dir iz nin klirk zo krol az Klirkampstirkrol: Here! di klirk allerklirkeniz hja to krol." in perfect Frisian which, you will not be surprised to learn, that was NOT an example of. If you did not say it properly, as demonstrated just now by yours’ truly, you would be drowned. Gulp.

This practice, of challenging unidentified people with a word or certain phrase that distinguishes one group of people from another is called a shibboleth. As good as this particular shibboleth is as a story, we really can’t find any other evidence that it holds any truth. Perhaps van Lennep heard it from somewhere, or he possibly misconstrued a similar story from not long after the events in this episode, when a big figure in Frisian history called Grutte Pierre is going to come onto the scene. The story about him is that he would use a Frisian Shibboleth against captive and potential enemies, making them say Bûter, brea, en griene tsiis; wa't dat net sizze kin, is gjin oprjochte Fries ('Butter, rye bread and green cheese, whoever cannot say that is not a genuine Frisian').

From 1479 there was increased feuding in the Schieringer dominated city of Bolsward in Westergo, with the death of Tjaard Jongema - the local, powerful haedling. When Tjaard died, he was an old man. According to the Biografisch Portaal van Nederland, what we know about Tjaard is that, as a Schieringer loyal, he helped kidnap a Vetkoper in 1410 and imprisoned him in Bolsward, but that the people of Bolsward quickly released him. In 1412, Tjaard Jongema he led a failed attack on the stins of a Vetkoper called Joost Hiddema, that resulted in the deaths of a fair few Schieringers.

Tjaard had been married to a powerful woman called Wyts whom a chronicler Pierius Winsemius described as “of a hard and masculine disposition”. The couple had a son, called Goslick, who was not yet of age. According to Pierius, when Tjaard died in 1479, his wife Wyts claimed the "right of government” in the name of her son, but the Bolsward council would not put up with “female rule” so instead chose to appoint Goslick’s cousin, the nearest male relative on the father’s side (remember ‘swirdsida’ had become more important that ‘spindelsida’). This was a bloke called Juw Jongema, a Vetkoper, who now became the guardian of both Goslick, the heir, and Bolsward, the city. Wyts was not happy with this and called one of her daughters’ husbands, a powerful Schieringer haedling called Sikko Sjaardema, to Bolsward. Sikko was able to drive Juw Jongema out of Bolsward and occupy it briefly, but his soldiers were very badly behaved, apparently egged on by Wyts who, according to a chronicler named Petrus van Thabor said “go to those houses, eat and drink there; for they are my enemies!” We imagine the party must have been fully Sikko. The citizens of Bolsward quickly revolted against Sikko and Juw Jongema was welcomed back into the city. Wyts was forced to run away from Bolsward in disguise.

Sikko and his troops holed up inside a fortress which belonged to his sister Swob. From there, they made themselves a nuisance within Westergo. As a result, the fortress was put to siege. Van Lennep tells a cracking story (which again, take with a grain of salt) about how Swob Sjaarda was able to put an end to the siege through a nice little bit of treachery. In 1481, Swob agreed to peace talks with one of the besiegers who had to cross a bridge to get to her. He asked that she swear his safety by promising him that it was ‘lauwa’ - A Frisian term for safe-conduct, or, if you will, the medieval Frisian equivalent of saying ‘safety’ in backyard cricket. After the meeting, her enemy departed back over the bridge but Swob called him back. When he turned around and crossed the bridge to her for a second time, she had him captured and thrown in captivity, telling him that she had given him safe conduct for the first bridge crossing, but not the second. Van Lennep then tells us that this is the origin of a Frisian saying ‘Swobbelauwa’ - meaning ‘Swob’s loyalty’, or a “false, deceptive promise.” It worked though, because soon afterwards the siege was lifted after an exchange of prisoners.

The feud between the Schieringers and Vetkoopers in Friesland continued however and in the 1490s both sides began to recruit outside mercenaries into their armies. Mol tells us that “since 1475, hoofdelingen who wanted to achieve military success could not do so without ad hoc hired professionals.” By this he was referring to mercenaries, and this was a dangerous development, which would ultimately spell doom for Frisian freedom. In 1491, the Vetkopers of Oostergo, who were mostly centered in the town of Dokkum, entered into an alliance with the city of Groningen. The Schieringers, who saw this alliance as a threat to Frisian Freedom, responded to it by attacking Dokkum. As a result, an army from Groningen came to their aid and occupied a large part of previously Schieringer controlled territory including the town of Sneek. They also threatened to capture the town of Franeker.

At this point, Goslick, the son of Wyts and Tjaard Jongema, in whose name Juw Jongema had taken over in Bolsward, went looking for outside help of his own on behalf of the Schieringers. He ran straight into the arms of Albert of Saxony, the lieutenant of Maximilian and governor of the Netherlands. Albert had been utilised by Maximilian in putting down the Flemish revolts and bringing order to a region that had so vigorously repudiated Maximilian and his constant demands for money. In those wars, Albert had used South German foot-soldiers who fought in a similar way to the Swiss, (which you can imagine if you cast your mind back to when we spoke about Swiss infantrymen before they killed Charles the Bold.) Think tight formations of blokes with long spears, turning themselves into spiky echidnas of death in the face of an assault. These 4,000 or so mercenaries, who had rocked up in the Low Countries in the 80s, did not just disappear when they had no work. Hans Mol tells us that “in the periods when Habsburg temporarily did not need them and could not pay them, the various Guard units also took on other jobs, including in the prince bishopric of Utrecht and the county of Cleves. In 1495 and 1496, Albert of Saxony had them involved in the Frisian party struggle – either to ally themselves with the city of Groningen and their Vetkoper friends or with the principal Schieringer hoofdelingen that had been cornered by Groningen and its allies – offering their services alternately to one party in turn for little money. In this way he did not have to pay them and was able to destabilise the situation in such a way that he could, precisely with their help, establish power there himself.”

In 1493, with the Frisian factional war raging, foreign mercenaries hanging around and imperial princes casting their gaze upon Frisia, Maximilian granted his charter to the Frisians which we mentioned earlier. This charter, remember, included a verbatim account of the counterfeit Chuck’s Charter, and importantly included reference to the office of potestas, that theoretical position somewhat akin to a governor of all of Friesland. Just the year later, with absolutely no end in sight to the internal violence still erupting in Central Frisia, Maximilian sent his envoy, Otto von Langen to tell them that they must choose a man to the position of Potestas otherwise he would do it for them. According to van Lennep, the Schieringer faction invited all of the Frisian estates to a meeting in Sneek, but the Vetkopers did not attend. A man amongst them, Juw Dekema, was elected to the role of Potestate and it was agreed that he would be sworn in in early 1495 in Bolsward, the recent flash point in the civil war and still held by Goslick’s Vetkoper cousin, Juw Jongema. The imperial envoy, Otto von Langen, is said to have arrived in Bolsward, ready to tell them that they must confirm the appointment, and ridden down the street to the eerie sound of children singing:

Heer Otto von Langen

Is nu hier gevangen;

Morgen zal hij hangen.

“Lord Otto von Langen

Is now a prisoner here

Tomorrow he shall hang.”

Shudder.

Vetkopers, meanwhile, were spreading word that Maximilian had ordered that no appointment be made until he had investigated the issue properly. Juw Jongema defied von Langen’s countermanding order that they choose a Potestas and refuted the election of Dekema. A quarrel broke out and von Langen had to flee to Deventer.

Still no resolution could be found as the internal fighting in southern Westergo and Zevenwoude - the southern part of Central Frisia - worsened. In 1495 Goslick returned to the field of battle alongside one of the most famous Saxon soldiers, a famous knight called Neithard Fuchs; together they campaigned across the region, wreaking devastation as they went. Van Lennep tells us that their infamy grew to the point of people in Holland flocking to join them, swelling their number to thousands. Sneek opened its gates to them, giving them a base of operations from which to cause havoc. Mol saying “Goslick, for his part, was not able to control his men, since he did not have enough money to pay them. The result was that the Landsknechte (referring to the German mercenary forces)...robbed and set fire to the surrounding countryside. This, in turn, incited the Grietenijen, the magistrates from the Zevenwoude area, to mobilise militia in defence of their region.

On January 13, 1496, things came to a head at Sloten, formerly a Vetkoper dominated town. Here, in the midst of winter, the largest, or at least most famed battle of the conflict took place. The German Landsknechte, led by Neithard Fuchs and accompanied by Goslick, stole their way along icy canals to connect with their allies and set up in battle order north of the town, ready to face the militias of Zevenwoude. Chroniclers veer wildly in their estimations of troop numbers, ranging up to eight thousand for the militias, though recent historical analysis of accounts puts the numbers for both sides in the hundreds, though a larger force from Groningen, allied to the Vetkopers, was not far away in Leeuwaarden and was supposed to be joining the fray.

The militiamen attacked the ordered troops in three different spots, inflicting some casualties but suffering more, due mainly to the fact that Fuchs had brought an cannon from Sneek and a fair few arquebuses with which to fire into the attacking Frisians. “The Frisian tactic was to surround the mercenaries and attack them from all sides, but with little success because their enemy kept rigidly in formation.”

The Frisians decided to regroup by crossing the frozen canal and hooking up with another contingent on the other side, then together having another crack at the troops of Fuchs, which by then had taken quite a battering. Many of their captains were gravely injured or dead. The Frisians had a plan to finish them off, perhaps even a good one, but for the fact that the ice was not solid enough to hold them. As they crossed the canal it collapsed, causing hundreds to drown. Those who did not were picked off by the mercenaries. In his chronicle Worp van Thabor wrote how much of a relief this was for the German and Schieringer troops: “For they themselves confessed and said: had the Frisians not drowned in the ice, they - the Schieringer troops - would have been slaughtered all over”.

Following the battle two priests went about to all the villages to record who had died. They came up with the number of 714 which, if true, has been calculated as about one sixth of all able bodied men from the villages of Zevenwoude. The German and Schieringer forces counted eight dead, but many injured, including Neithard Fuchs.

As for Goslick, he could not, once again, pay his soldiers after the battle and they quickly rose in mutiny, causing him to escape and flee, once again, to Albert of Saxony. With his support, though, Goslick successfully recaptured Bolsward and the Vetkopers and Groningers were pushed out of Westergo.. He re-entered the town and took his cousin Juw Jongema, who had remained in command there, prisoner. Juw’s ransom of 600 guilders was paid for his release, after which Goslick killed him by his own hand. Brutal!

Following this time Goslick and other Schieringers pushed for Albert of Saxony to be elected to the position of Potestas. There are a couple of important factors in Albert’s interest in the Frisian territories. Firstly, he was owed a lot of money by Maximilian, so had leverage in getting what he wanted and, secondly, he was trying to secure lands for his sons to rule. The idea firmed that Frisia would be those lands. As mentioned earlier, he would use the German mercenaries in the employ of different feuding parties, deliberately sowing continued chaos and instability. Well after the Battle of Sloten he had put them in the employ of a Vetkoper Haedling and ally of Juw Jongema, Tjerk Walta. By 1498 the Schieringers were so cornered and under threat that they appealed to Albert to come in as their protector. He swiftly accepted their plea and in April they recognised him as their Potestas. Oh dear, the proud Frisians, who for centuries had zealously guarded their freedoms against the ambitions of foreign princes, now meekly invited one in.

Albert of Saxony arrived in Frisia, brought the mercenaries back into his employ and sent a force under the command of Neithard Fuchs and another captain, Wilwold von Schaumburg, to bring Ostergo and Groningen to heel. After they had done this, they set about subjugating the rest of Central Frisia, joined by about 500 other local troops led by Schieringer Headlingen. On June 10, 1498 near Warns and Laaxum, an army of the Frisian popular militia was soundly defeated by the now Saxon forces. Thereafter, Fuchs and Schaumburg could complete their occupation of Central Frisia uninhibited, on behalf of Potestas Duke Albert of Saxony, the new lord and protector of Frisia. With his and, shortly thereafter, his sons’ ascent to the lordship over Frisia, the ancient, if self promulgated, privilege that was Frisian Freedom was, finally, (forever?) finished. The endless conflict, however, was most certainly not. Many Vetkopers fled towards Guelders, who were in the throes of a war against the Habsburgs that we will get into in the next episode. The Vetkoper-Schieringer civil war, which had raged for over a century and a half, morphed into a kind of war of independence, waged against the foreign rulers that their constant bickering had finally allowed in. But that’s all for future episodes of… History of the Netherlands.

Sources used:

“Frisonica libertas: Frisian freedom as an instance of medieval liberty” by Oebele Vries

“Graaf Willem II van Holland en de Friese vrijheidslegende”, by A. Janse, in Negen eeuwen Friesland‒Holland. Geschiedenis van een haat-liefdeverhouding, eds. P.H. Breuker and A. Janse (Zutphen: Walburg Pers, 1997), 77–86.

Frisian Land Law: A Critical Edition and Translation of the Freeska Landriucht by Han Nijdam

“The end of Frisian freedom by its confirmation: The Frisian Imperial Privilege of Emperor Maximilian I and its background. Part I: The first charters” by W W K H Engelbrecht in Scandinavian Philology, 2024, vol. 22, issue 1, pp. 153–171. https://doi.org/10.21638/11701/spbu21.2024.110

‘Friesland‘, in Medieval Germany: an Encyclopedia, ed. J.M. Jeep (New York: Garland, 2001), 252–6.

The Frisian Popular Militias between 1480 and 1560 by Hans Mol

‘When the Shore becomes the Sea’ by Yftinus van Popta

“Church Foundation and Parish Formation in Frisia in the Tenth and Eleventh Centuries” by

de Langen, Gilles; Mol, J. A, in The Mediaval Low Countries, 4, 1-55 https://doi.org/10.1484/J.MLC.5.114814

Frisian Land Law: A Critical Edition and Translation of the Freeska Landriucht by Nijdam, H., Hallebeek, J., & de Jong, H. (Eds.). (27 Feb. 2023). Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004526419

“The Frisians as Chosen People. Religious-patriotic Historiography in Fifteenth Century Frisa”. by Mol, J., & Smithuis, J. (2021). in Amsterdamer Beiträge zur älteren Germanistik, 81, 172-207.

De stinzen in middeleeuws Friesland en hun bewoners by P.N. Noomen.

De geschiedenis van Nederland, aan het Nederlandsche volk verteld. Deel 1 (1880) by Jacob van Lennep

“Greate Pier fan Wûnseradiel” found here https://web.archive.org/web/20081207005139/http://www.wunseradiel.nl/index.php?simaction=content&pagid=289&mediumid=1

“Jongema, Juw” in Biografisch Portaal van Nederland by A.J. van der Aa

“Juwsma, Wyts” by Martha Kist in: Digitaal Vrouwenlexicon van Nederland. URL: https://resources.huygens.knaw.nl/vrouwenlexicon/lemmata/data/Juwsma [13/01/2014]

“Sjaarda, Swob” by Martha Kist in: Digitaal Vrouwenlexicon van Nederland. URL: https://resources.huygens.knaw.nl/vrouwenlexicon/lemmata/data/Sjaarda [13/01/2014]

“Jongema, Goslick” in Biografisch Portaal van Nederland by A.J. van der Aa